The (Geo)Politics Of Precious Metals

Michael Hudson, a renowned economist, discusses the rising price of gold and its geopolitical implications.

Since 2018, gold prices have nearly tripled, driven by central banks’ increasing demand, particularly in response to U.S. sanctions and asset seizures, such as the $300 billion in Russian reserves frozen by the West. This trend reflects a global shift away from reliance on the U.S. dollar and euro, with gold seen as a safer alternative. „Gold is being seen as an alternative to dollar or euro-denominated assets,” Hudson explains, emphasizing that economic decisions are deeply intertwined with political concerns.

Hudson argues that the gold market is unique and has been historically manipulated by the U.S. to maintain the dollar’s dominance in global reserves. He notes that, unlike other commodities, gold’s price was artificially suppressed for decades to keep global financial reliance on U.S. Treasury securities.

„The aim of this was political—to keep the world viewing the U.S. dollar as the most secure form of international reserves,” he states. However, as trust in the Western financial system declines due to excessive monetary policies and sanctions, nations are turning to gold. The recent sharp rise in gold prices signals the breakdown of this controlled system.

A major concern Hudson raises is the discrepancy between the actual gold supply and the financialized gold market, where much of the traded gold is merely paper-based. The leasing of gold by central banks to private dealers has created a situation akin to a financial bubble, with more claims on gold than the available physical supply.

„This gold drain to satisfy the recent price rise has seriously depleted gold reserves,” Hudson warns, suggesting that when investors demand actual gold rather than financial derivatives, the system could collapse.

He compares the situation to a bank run, where too many people seek to withdraw their assets at once, revealing the fragility of the system.

Looking ahead, Hudson speculates on the potential for a financial restructuring where gold plays a central role. He suggests that countries disillusioned with the Western financial order may seek a new monetary arrangement based on gold or other tangible assets.

„People have wanted to hold gold bullion because it’s tangible, and you know how much you have,” he says, highlighting the loss of trust in fiat currencies.

As global demand for gold continues to surge and supply remains constrained, this could signify a broader transformation in international finance, challenging the longstanding dominance of the U.S. and European monetary systems.

Key Takeaways:

-

Central banks are stockpiling gold due to fears of U.S. sanctions and asset seizures, signaling distrust in Western financial institutions.

-

The U.S. has historically suppressed gold prices to maintain the dollar’s dominance, but this control is weakening as gold prices soar.

-

The gold market operates differently from traditional commodities, with a significant portion of its trade based on financial instruments rather than physical reserves.

-

A potential „gold run” could occur if investors demand physical gold, exposing the lack of sufficient reserves and destabilizing the financial system.

-

The shift toward gold suggests a potential monetary realignment, where countries move away from reliance on the dollar and fiat currencies in favor of tangible assets.

Michael Hudson is interviewed by Geopolitical Economy Report editor Ben Norton.

Transcript

(via GeopoliticalEconomy.com)

(Introduction)

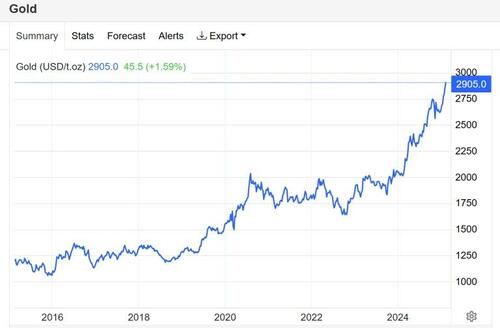

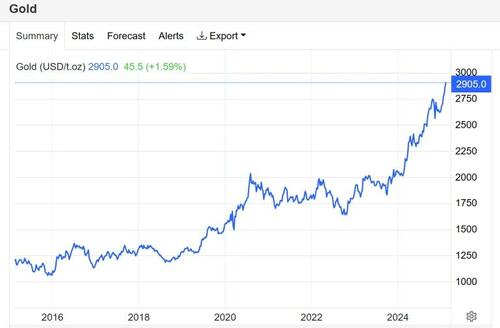

BEN NORTON: The price of gold has been skyrocketing. Since 2018, the price of gold has nearly tripled. This has caused a big debate around the world about why this is happening. There are, of course, several different factors.

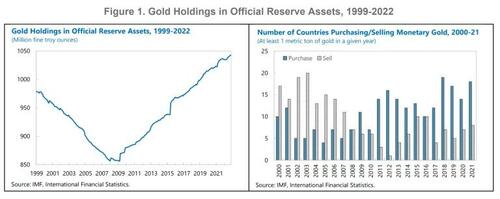

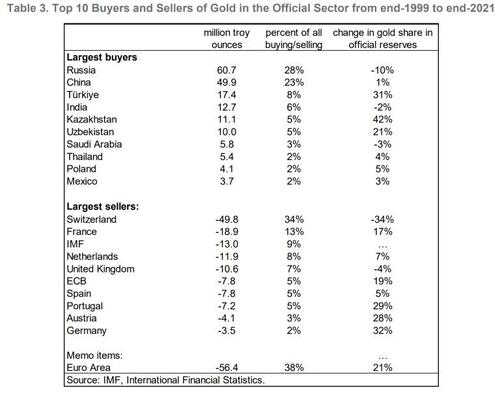

One of them is that central banks around the world have been buying more and more gold, especially with the threat of sanctions from the United States. One-third of all countries on Earth are under US sanctions, including 60% of low-income countries.

The war in Ukraine has only accelerated this, as the US and the EU seized $300 billion dollars and euros worth of assets held by Russia’s central bank. This has scared many other countries’ central banks, which fear that they could be next to have their assets seized by the West.

Gold is being seen as an alternative to dollar- or euro-denominated assets.

But it’s not just central banks. There’s also a lot of private demand, especially as there was a lot of inflation coming out of the Covid pandemic.

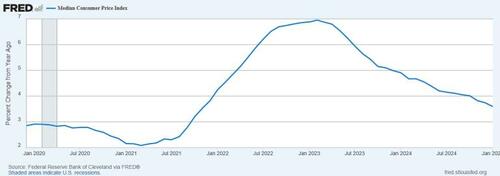

What’s interesting is that, typically, gold is seen as an inflation hedge. And when inflation increases, the price of gold tends to increase. But in the past two years, inflation has come down, yet the price of gold has continued to skyrocket.

So why is this happening?

Well, today I had the privilege of being joined by the award-winning economist Michael Hudson, and he explained why the price of gold continues to rise, and what the implications could be for the entire global economy, and the politics of gold — because, as Michael often stresses, you cannot separate economics from politics.

So here are a few highlights of Michael Hudson, and then we’ll go straight to the interview.

(Highlights)

MICHAEL HUDSON: Demand for gold, as I said, has been far outstripping the supply for many, many years now. And as we’re taught in Economics 101 textbooks, when demand outstrip supply, prices go up.

But that hasn’t been happening with the gold price until just the last few months. And the question is, why hasn’t it happened?

…

Well, the obvious answer is that the gold market isn’t like regular commodity markets.

…

So the United States has sought to keep gold prices down ever since it was revalued in 1971… The aim of this was political: to keep the world viewing the US dollar, meaning essentially US Treasury securities, as the most secure form of their international reserves.

It’s secure in the sense that, unlike other countries, the United States can simply print the dollars. It can’t go bankrupt.

…

People like to say gold is an inflation hedge. But you could say eggs are an inflation hedge, or pork is an inflation hedge.

The point is, the real problem is the US balance of payments deficit pumping dollars into the world.

You’ll pay dollars to an exporter, from China or Germany — when there was still a German industry — and they turn the dollars over to their central bank, and the central bank would then say, “What are we going to do with these dollars? If we don’t send them back to the United States, our currency is going to go up against the dollar, and that is going to make our exports less competitive. So we have to keep our currency, our exchange rate, down; and we do that by buying Treasury securities”.

It has always been political. And the newspapers don’t want to talk about politics, because if they talked about politics, all of a sudden people would realize the Western political and economic system cannot last in the way that it’s structured now.

When you talk about politics, you realize the game is over for the West.

* * *

(Full interview)

BEN NORTON: Hi, Michael. It’s always a real pleasure having you. The last time we had a discussion, we analyzed the effects of Donald Trump’s tariffs, or his threat of tariffs. And you warned that it could cause a global financial crisis, as countries won’t be able to get the dollars they need to pay off their dollar-denominated debt.

After we had that conversation, you raised some other points about the gold market that you wanted to talk about, and I thought that would be a great separate episode.

So why do you think we’ve seen this massive shift, the near tripling of the price of gold in the past seven years?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, we’ve been talking for many years now about how the international financial system works, and central bank reserves, and de-dollarization, and the split of the BRICS away from the West.

And that’s what my book Super Imperialism was about, how America was driven off the gold standard because of the balance of payments drain from the Vietnam War and for world military spending, up to 1971. The entire U.S. balance of payments deficit from the Korean War in 1950, all the way through the ‘50s, the ‘60s, and into the ‘70s was military spending.

The result was that the United States had, every month, to sell the accumulation of dollars that ended up in France, Germany, and other countries. The dollars spent in Vietnam that were exchanged for local currencies ended up in French banks, because Southeast Asia was a part of the French empire; and the French banks sent these dollars to Paris, and General [Charles] de Gaulle would then cash in the dollars [for gold] every week.

Until 1971, every printed dollar — your dollar bills in your pocket — had to be backed, by law, 25% by gold. So we were watching the American gold supply go down, down, down to the gold cover.

Every week, on Friday morning, when the Federal Reserve gold report would come out on Wall Street in the mid ‘60s, we were all saying, “When is the breaking point going to come?”

Well, it came in August 1971. At that time, the US government thought, “This is terrible. We have controlled the whole world financial system ever since World War One, by holding gold, and that was what other countries used to have their monetary reserves. We have controlled other countries’ ability to run budget deficits, to fund their own economy with gold; now we don’t have it anymore”. And there was a lot of hand-wringing.

I wrote my book Super Imperialism to say that this is not going to interfere with the American empire, because if countries, central banks, governments can’t buy gold, they had only one big alternative at that time, and that was to buy dollars.

And how do they buy dollars? They buy US Treasury bonds, Treasury notes, short-term Treasury securities. They put in their money and hold it in the form of US debt.

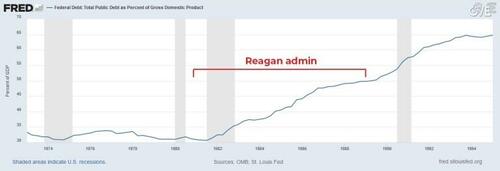

As they got more and more dollars, they spent more and more money buying US debt. And that became an increasing way of how the United States funded its own budget deficits.

Who bought the bonds to fund these? Increasingly, central banks. So the United States found this is what some people called the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar.

When other countries run a balance of payments deficit, they have to devalue. The IMF comes in; they say, “Lower your wages; impose poverty to squeeze out enough money to pay the bondholders”. But the United States can keep printing the money.

So, what can other countries do? They don’t have an alternative.

Well, you’ve seen increasing pressure to create an alternative for the last decade or so. That’s what your and my discussions and your site has been about.

Other countries want to de-dollarize, and the United States fears, “What is going to be the alternative?”

Well, to some extent, we know they’re buying each other’s currencies. They’re buying yuan, rubles; doing trade and investment in each other’s currencies; to avoid having to use the dollar, and having to take the risks that Venezuela took, Iran, and Russia, of just having the dollars confiscated.

But still, there is an idea that gold is a kind of asset that the whole world has been able to agree on, along with silver, for the last 3000 years, as the monetary base.

How are you going to get countries all over the world, from North America, to Europe, to Asia, all to agree on what to hold?

Well, they’re trying to come up with an agreement now, and they realize that you can’t have a BRICS monetary system until you have a whole political integration of the BRICS. So that’s not going to be an alternative for right now. So countries have been buying gold.

Well, the private sector is watching all of this. They’re listening to your show, and what I’ve been writing about, and they say, “We’re in a situation now, just like the world was in the late ‘60s, going into the 1970s, when finally the gold price rose beyond the ability of the United States to keep it down to $35 an ounce”. So private investors have got into the gold market.

This is what makes the gold market not simply talk about commodities, how to get rich; it talks about how the world economy is being restructured, and its monetary relations, and what the politics are.

But what I’m going to talk about today is what is happening that makes the gold market so political and so unique, that something very strange is happening there.

On Monday, February 10th, the week started with gold rising to over $2,900 an ounce. So we’re on the verge of it going up to $3,000 an ounce. That’s a quantum leap.

If you look at the statistics for gold mining throughout the world, the supply and demand of gold, demand has been far outstripping the supply now for 20 or 30 years.

We’re seeing now an effect very much like a run on the bank. But that run on the bank has actually been occurring for a few decades.

So the question that you have to ask to begin with is, why did it take so long, until just this year, for gold to begin to go up in price, after it stagnated for a decade?

We’ve seen, in the last decades, the central banks have devoted a steady rise in the proportion of their reserves that they hold in gold, and proportionately less of their reserves in the form of U.S. dollars.

They’re still holding more and more dollars every year, because the United States is running such a large balance of payments deficit that it’s pumping dollars into the world economy.

But other countries are not just recycling these dollars. They’re spending more and more of the dollars they get on gold, as a kind of safe haven for them: something that is solid.

Gold is an asset that doesn’t have a debt attached to it. If you hold a gold coin, or a gold bar, that’s a pure asset — no debt at all.

But if you hold a Treasury bond; that’s a debt, a debt of the United States. And if it’s a debt of the United States, it’s like your bank deposit is a debt of the bank to you.

If the US goes under, like a bank goes under, or if it just refuses to pay, then you’re out. And there’s something ephemeral about all of this.

Well, if you look at the trend of gold prices, it stagnated in a very narrow range from about $1200 to $1400 an ounce for a few years, from 2015 to 2019. It was all in that range.

I spent a lot of time in Europe and Asia at that time, and all of the government officials I talked to, the financial funds, all said, “You know, we’re buying more and more gold, because this system can’t last, politically, the way it is”. But the price didn’t go up.

Then, during the Covid years, from 2020 to early 2023, once again, there was a stagnation, a range from $1800 to $2000 an ounce. That’s a pretty narrow range — you know, a low range, a little step function to a new range, and then very gradually drifting upward, but not anywhere near as fast as the actual demand for gold was.

Well, finally, in the last half-year, we’ve seen the gold price rise all out of range to, as I said, nearly $3,000 an ounce.

So the question is, are we in a new range for gold, or is the price going to go higher?

With so many people buying the rights to hold gold — you’ll buy a gold fund, and you’ll pay money into the gold fund, and that has securities in gold; or you’ll buy gold and you’ll store it with a bullion dealer, because you don’t want to keep it at home, because it could get stolen, or who knows what will happen.

Well, where is all this gold going to come from, physically, to meet the demand?

During the last half a century, quarter century, there has been a rising private investment boom in gold, because people can look at the trend — more and more, excess demand over the supply — and they can see that this is an unstable situation.

So to understand it, you have to understand how unique the gold markets are. And I want to talk about that today, not simply as an exercise, but to show what the politics behind the gold market are, and what it means for how the world economy is being restructured.

Suddenly, gold is more than just an investment vehicle. There have always been gold bugs who don’t understand, “How is it that the government can just print money? We don’t understand. We’re going to just try to buy gold, and there should still be the gold standard, like there was in the 19th century”. There are all these crazies on the right wing, libertarians, who don’t trust government.

But now we’re talking about demand not just from the crazies, but from regular funds that are looking at the trends, and they realize that there’s a pile-on effect that is occurring. Everybody suddenly is moving into gold.

You’ll find the advertisements all over the internet, when you watch YouTube shows, there is very often an advertisement for gold on there. And obviously, more and more people are doing it.

So the question is, is all this just a bubble, or are we moving towards a new and even higher long term plateau? Is there a change occurring in the world’s financial and monetary system? Politically?

Well, I’m going to explain what is happening.

Demand for gold, as I said, has been far outstripping the supply for many, many years now. And as we’re taught in Economics 101 textbooks, when demand outstrip supply, prices go up.

But that hasn’t been happening with the gold price until just the last few months. And the question is, why hasn’t it happened? And why have the gold prices suddenly begun to escape from their former narrow range and risen so fast, since last autumn?

Well, the obvious answer is that the gold market isn’t like regular commodity markets. And even regular commodity markets don’t operate in the simple way that popular media and textbooks say.

One reason for that is that, for the last century, the price of gold has been regulated by central banks, mainly by the US Treasury, ever since Franklin Roosevelt revalued gold to $35 an ounce in 1933.

That lasted until President Nixon took the US off gold in 1971. And, as a result of the war, and as I said, US officials were very frightened that the US was no longer able to control the price of gold. Hence the key to the whole world’s money creation that it needs to finance how its economy operates.

The US thought, “Well, other countries are now going to take gold, and we’re not going to keep up with them, and there goes our leverage for imposing power in institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, that were all put in place 1944, 1945, at the end of World War Two”.

But that didn’t happen, for the reasons that I explained in Super Imperialism, my book in 1972. There really weren’t many alternatives large enough to put foreign money in.

So instead of cashing in their dollar inflows by buying gold, foreign central banks just bought Treasury securities. And as I said, that funded the rising portion of the US domestic budget deficit.

Well, the dollar glut was run up mainly, as I said, by military spending. And I worked for a year with Arthur Andersen, the accounting firm, and Chase Manhattan Bank, showing this. And I became a consultant to the US government, explaining this phenomenon, during the 1970s.

This is not something that is taught in economics courses, because it’s politically sensitive, and economics tries to be “apolitical”, because if you see how political economics really is, you have a different approach to politics.

So the United States has sought to keep gold prices down ever since it was revalued in 1971. Gold prices went up pretty quickly to about $700, $800 an ounce. Then finally, by the mid 2010s, into $1200, $1400, you know, gradually going up.

The aim of this was political: to keep the world viewing the US dollar, meaning essentially US Treasury securities, as the most secure form of their international reserves.

It’s secure in the sense that, unlike other countries, the United States can simply print the dollars. It can’t go bankrupt, and be unable to pay the debts, because unlike other countries that have debts in a foreign currency, the US debt is in its own currency in dollars, and it can just keep printing them.

BEN NORTON: Very well said, Michael. There’s so much we could respond to.

We talked about central bank demand for gold. But I think another important factor here is inflation, because traditionally gold has been seen as an inflation hedge.

When you have moments of high rates of inflation — for instance, coming out of the Covid pandemic, as the economy reopened in 2022, consumer price inflation was very high in the United States and many countries, because of the supply chain disruptions.

So as inflation increased in 2022, you could see that, in October, the gold price was around $1,600, and it increased pretty substantially to almost $2,000 in the spring of 2023.

What happened then is that, in early 2023, the inflation peaked, and the gold price went down, as inflation went down, because it’s of course seen as an inflation hedge, so it makes sense that they would tend to move together.

However, then something very strange happened. In October 2023, the gold price reached a low of around $1,850, and since then, consumer price inflation has continued to fall. But that relationship broke, and instead the gold price skyrocketed by another thousand dollars to around $2,900.

So, Michael, that relationship has now ended, it’s broken. Why do you think that is?

MICHAEL HUDSON: I don’t think there’s a causal relationship, there at all. That’s my whole point.

People like to say gold is an inflation hedge. But you could say eggs are an inflation hedge, or pork is an inflation hedge.

The point is, the real problem is the US balance of payments deficit pumping dollars into the world.

You’ll pay dollars to an exporter, from China or Germany — when there was still a German industry — and they turn the dollars over to their central bank, and the central bank would then say, “What are we going to do with these dollars? If we don’t send them back to the United States, our currency is going to go up against the dollar, and that is going to make our exports less competitive. So we have to keep our currency, our exchange rate, down; and we do that by buying Treasury securities”.

It has always been political. And the newspapers don’t want to talk about politics, because if they talked about politics, all of a sudden people would realize the Western political and economic system cannot last in the way that it’s structured now.

When you talk about politics, you realize the game is over for the West. And so of course they don’t. They want to make it appear micro, “Oh, there are some people who just try to look at inflation rates”.

Some people really believe this. They believe the textbooks. They’re gullible. Most investors in gold, I have to say, are gullible, but there are other people who are actually looking at reality, and they can see, this system can’t last.

In the end, the people who don’t trust gold are going to win.

I’ll give you an example. In 1973 or ‘74, Herman Kahn and I went to the White House for a meeting with the US Treasury. And I was explaining to them how the Treasury bill standard worked.

Well, what I said was something that, certainly, they didn’t want to hear. I said, “Gold is ultimately the peaceful metal, because it was the US running out of gold that threatened to stop it from spending the military costs of the war in Southeast Asia, and all over, the 800 military bases that it has over the world”.

If you have gold continue, and if Nixon did not go off gold, then America would very quickly lose all of its gold stock, as the cost of waging war against the rest of the world, of keeping its unilateral military power.

It’s not power because it’s a democracy; it’s not power because people love it; it’s because American power is the ability to hurt other countries, to bomb them, to finance regime change, and to threaten other countries. And that costs a lot of money to keep threatening.

That’s part of the whole crisis that we’re seeing now, and you’re all of a sudden winding down what has been, as Trump and [Elon] Musk have been saying, you’re winding down what has been absorbing an enormous part of the American budget, pushing it into deficit.

And these are deficit bugs. They’re not modern monetary theorists; they believe that deficit spending is bad, not that deficit spending is how the government provides money into the economy at large.

So, there’s a whole conflict of monetary theory that’s going on now. So you could say that this whole fight over gold and gold futures reflects the whole idea of what is going to be the basis of American military policy, and American foreign policy, and geopolitics.

Are we going to be in a constant war against the whole rest of the world? Or are we going to try to make peace with Russia, China, and Iran, and just focus against countries that we can really beat up, like Canada, England, Australia, Japan, South Korea?

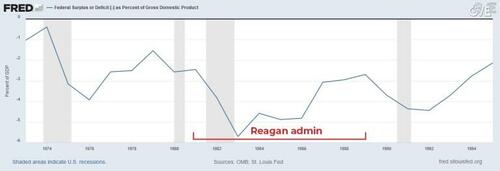

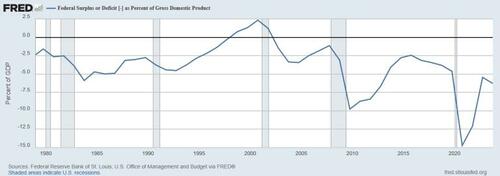

BEN NORTON: Yeah, what’s also ironic is that Trump talks about cutting the deficit, but he’s also cutting taxes on the rich, which will likely increase the deficit, which is exactly what Ronald Reagan did.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Right! He is not quite — ha! That’s the unstated part. We all know what he wants.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, exactly. It’s the same thing that Ronald Reagan did. You know, Reagan said he was going to cut government spending, but, actually, the US deficit as a percentage of GDP increased significantly under Reagan.

Ironically, it was the neoliberal Bill Clinton administration that actually reduced the deficit, and for the first time ever since, the only time ever since, the US actually had a budget surplus.

But what’s interesting, Michael, is that you have been associated with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), and you’re not a gold bug.

But what you’re saying here is that there is an element — you’re not arguing that the dollar should go back to the gold standard. That’s not what you’re arguing.

You’re saying that there have to be limitations to the amount of money printing, by having some kind of a link to reality [and the real economy].

MICHAEL HUDSON: Modern Monetary Theory explains how to finance the domestic budget deficit.

One thing Modern Monetary Theory theory cannot do, when you create money, is you can’t create foreign currency.

[The United States] can create dollars to spend into the economy. You don’t have to borrow these dollars from wealthy bondholders and investors. You can simply print the money. You don’t have to levy taxes, because that’s the essence of paper money.

But, when it comes to foreign spending, especially military spending, [the United States] can’t print Chinese currency to finance your spending in Asia. [The United States] can’t print rubles. You can’t print other currencies for spending abroad.

So Modern Monetary Theory refers to a domestic economy, not to foreign money. It’s a theory of domestic money.

Gold is a constraint on money creation. It all goes back to the awful, awful theories of David Ricardo, the bank lobbyist, in Britain in 1809 and 1810, when he was testifying before the Bullion Committee and saying, “We need to keep wages down. We need to keep the economy poor, so that the wealthy creditors can get enough money to control the world, and reduce everybody else to abject dependency. So we’re against paper money. Paper money is inflationary. If you only use gold and silver, which the rich people have, then we can operate the whole world”.

Well, he didn’t say it just in those words, as you can imagine, but his arguments were against creating paper money. This was the antithesis of Modern Monetary Theory.

Ricardo spelled out in great detail exactly what the principles of the International Monetary Fund are have been since 1944 and ‘45, that, if you don’t let countries create their own paper money, and force them to have hard currency, gold, or US dollars, then they can’t afford to hire more labor; they can’t afford to invest. They’ll be completely dependent on countries that can act as is creditors.

Again, that’s what I explain in my book Super Imperialism, how this whole system came in.

I’m writing a book now — I’m on the last two chapters — on the political alliances of bankers from the Crusades up to World War One, where you have the whole attempt at hard money.

This is what caused a rupture in American politics in the 1870s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s.

BEN NORTON: Yeah, at the end of the 19th century, the famous populist US politician William Jennings Bryan said that the financial class wanted to “crucify mankind on a cross of gold”.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Remember, the creditors after the Civil War wanted to roll back prices. They said, “Well, there’s been inflation during the Civil War. And that means that all of our bondholders, we don’t have the same purchasing power over labor. We have to reduce labor’s wage rates and make them poorer and poor, so that we can get richer and richer, and we do this by forcing gold down. You need unemployment”.

They were, just like the Federal Reserve says, “We need unemployment, hard money, to keep wages down, so that employers can make more profits from hiring cheap labor, basically”.

This is a class war of the financial sector against the economy at large, against industry. Finance capitalism has become antithetical to industrial capitalism. That’s what you and I have been talking about in these shows.

It all goes back to Ricardo saying, if you take away the government’s ability to run deficits and spend money into the economy, then you’ll be dependent on the rich people to supply the money.

So when President Clinton finally ran a budget surplus in 1998, what happened? That meant that the government was not spending money into the economy. People had to go to the banks and borrow, and pay interest to the banks.

That’s what the financial sector wants. It wants to get interest to force the economy at large to pay interest, to get the money that it needs to conduct business, and employ labor, instead of having the government simply provide, printing the money, without interest. The inflationary effect is identical.

It’s no more inflationary to print money than to borrow from a billionaire, who isn’t going to spend money on buying [more] eggs, in any case, and “printing” the money that way.

So there’s a whole fight over, what is the source and the use of money in an economy today?

That has been pretty much not discussed in the popular press, but that’s what Modern Monetary Theory is all about. That was fought against by the financial sector that wanted to control money by the wealthy classes, by the financial sector, and by the banks, not by the government for the public interest.

The [US] government position, Democratic Party position or Republicans, is that money is to be created to make money for the wealthy financial sector, not for the economy.

Modern Monetary Theory is that we should create money to promote actual economic growth and rising living standards, not simply create money in a way that makes money for the financial sector and the billionaires.

All of this political argument lies behind the restructuring of monetary policy that we’re going to be seeing in the next few years, triggered by this gold meltdown.

BEN NORTON: Very well said, Michael. There’s so much we could respond to, but I want to go back a little bit to talking about the gold market.

Something that you were emphasizing is how different the gold market is from other markets. You were talking about how, you know, the actual economy works very differently from what is taught in textbooks.

You emphasized that the gold market in particular is different from other commodity markets. So can you talk more about that?

MICHAEL HUDSON: So, the important key to understanding just how all of this was accomplished is to see how complex the world’s financial commodity exchanges where gold prices are set are, and what’s their relationship to actual commodity dealers, which is where individuals go to buy gold.

Central banks can buy gold from each other. Investment funds, hedge funds, individuals, jewelry makers, etc. buy gold from bullion dealers.

Well, there’s a general impression that when people, or central banks, or mutual funds, buy gold, they place bids in a market, something like the Commodity Exchange, COMEX.

But that’s not really where people buy and sell gold.

In a commodity exchange, this is really a gambling venue. You bet on whether the price of a stock or a bond, or gold, or a commodity — copper, or wheat, or any other commodity — is going to go up and down.

So a commodity exchange is [where you go to] bet on where prices are going to go.

These dealers who are buying and selling options for grain prices — and where is the stock market, or the S&P 500 going to go — they’re not actually going to buy wheat, or gold, or the stocks; they’re putting a bet on which way prices are going to go.

That bet is supposed to reflect what’s happening in the real world. There’s supposed to be some physical, tangible basis for all of this.

So I want to take a minute to explain. [The asset manager] Vanguard has a site that talks about puts and calls, and selling short, and options, and that has a vocabulary all its own.

I’m going to quote what Vanguard says:

When you buy a call option, you’re buying the right to purchase a specific security at a locked-in price (the “strike price”) sometime in the future [at a given date].

If the price of that security rises, you can make a profit by buying it at the agreed price and reselling it on the open market [in the exchange] at the higher market price.

When you buy a put option, you’re buying the right to sell someone a specific security at a locked-in strike price sometime in the future.

So suppose, the price of gold is at $1,250. You can say, “Well, I’m going to sell it to you at only $1,200”. Well, if the price falls, you can actually make a profit by buying it on the open market at the lower price, and then exercising your put option at the higher price. That sounds complicated.

BEN NORTON: Just to simplify for people — you had a good description — the very simple explanation is, if you buy a call, it’s because you think the price will go up; if you buy a put, it’s because you think the price will go down. So, call up, put down.

As you said, these are essentially financial bets. This is options trading.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, the question is, during the 2010s, why, when everybody was saying, “This trend can’t go on; the price of gold has got to go up”, why would somebody come in and keep selling gold at a lower price forward, saying, “In three months, we’re going to sell you gold at $50 an ounce less, or $25 an ounce less”. Who was doing this?

I don’t know any private investor that would have come and done that, because they said, “Well, we think the price is going to go up, instead of going down; that’s the long-term trend of gold”.

Well, the explanation is this selling of gold forward was done by central banks, mainly by the US Federal Reserve and Treasury, acting on behalf of the Treasury, or the Bank of England.

When you buy a put or a call, you have to pay money for the options. And there used to be, you would look in the newspapers, and here’s how much it cost to buy an option for treasury bonds, a price for stocks, or for gold.

When you sell the right to buy gold at, let’s say the same price, or a dollar or two less, then people will pay you for that option to buy it at the same price in three months, or six months. That’s a source of revenue.

So the US Treasury, and the Bank of England, were actually making money selling gold short. And when you keep promising, you have so much money, and you’re such a large participant in the market, you’re sort of like George Soros when he broke the Bank of England. You can make the market by being so large.

When you come in and you keep selling gold short, way beyond the demand, you’re overwhelming the market, and that holds the price down.

Even though more and more people may be buying gold, the United States and England are making money by essentially engaging in this market manipulation as a source of revenue.

That is one of the factors that was holding down [the price of gold].

Well, central banks also have, in fact, been selling gold short for many decades now. And they’ve been making money by it.

As I said, to buy this option, to buy gold at a fairly low price when you think, “Well, certainly the market is going to go up for gold; the price must be going up for gold, because everybody is buying it. I’m going to buy this option”.

And it just didn’t work. A lot of people, pessimists, tried to do this, and they were overwhelmed by the central banks’ selling.

Most options are not exercised, because central banks keep selling forward again, and again, and again. That is what held down the price of gold for many decades. It kept the price from rising, because future buyers can always buy the other end of a short sale, at a lower price.

The supply and demand wasn’t just in the private market; it wasn’t just among central banks; it was a manipulated market.

So it seems that this gold drain, to satisfy the recent thousand dollar an ounce price rise that we’ve seen, has seriously depleted gold reserves. The Treasury has actually had to sell them.

This is another aspect of the market. That’s the gold dealers.

Suppose there were not a commodity exchange, to set the prices for contracts.

Well, the demand for physical gold has been running ahead of its supply. So, central banks have been leasing the gold to gold dealers.

In other words, the central banks have felt, you could call it hubris. They said, “Well, we’re always going to be able to keep the price of gold down”. So gold dealers are buying gold, and selling it to their customers, who expect prices to go up.

So the gold dealers will say, “Lease us a ton of gold, at this price. We will pay you to lease it so that we can send it to customers”.

If the price doesn’t go up, you know, at a certain point, the customers will say, “OK, I didn’t make the profits in gold that I made in the stock market, or in the bond market”.

Remember, after the Obama bank crisis in 2008-2009, the whole quantitative easing came in, and interest rates were so low that it spurred an enormous stock market boom, and the biggest bond market boom in history.

Why would people want to buy gold after 2009, when gold prices are going up gradually, but stock prices and bond prices were going up so much more?

So the rival to gold was this artificial boom created by quantitative easing and, low interest rates. So that’s part of the equation.

Central banks were happy to lease the gold to gold dealers. They made money from this leasing, just like you’d lease a car. You would give them the gold; they would have to give it back at a specified date.

You say, “OK, we’ll lend you this gold for a year, and at the end of the year, you’ll have to give it back, but you can hold it, and do what you want at that time”.

Well, the gold dealers would then turn around and sell to the private investors — maybe to central banks, too — the gold that they’d leased. At the end of the year, they would say, “We’ll take out another lease, and we’ll lease now for two tons”; then later, you know, for three tons.

So the central banks would keep leasing out the gold, ton after ton, to the gold dealers.

Well, that meant that the US would send gold, physically, from Fort Knox to the gold dealers — largely in London, which was sort of the gold trading center.

Just like the gold market after World War Two, when the United States held down the price of gold in the market. That was in the London gold exchange, that they were holding it all in.

So, the US and England kept leasing gold, making money that way from the dealers, and selling gold short, and making money off the purchase of the commissions. And that became a good source of financing.

If you do the accounting, Fort Knox would have a claim for payment on the gold dealers for leasing this gold. And, that was a way for Fort Knox and the Treasury to make money.

But their aim wasn’t simply to make money; it was to keep down the price of gold, so that gold would not reemerge as a rival to the US dollar.

That’s what drove, this whole system. And that was the motivation for the United States. It was political.

BEN NORTON: Michael, by the way, just, for people who don’t know, Fort Knox is the Department of the Treasury’s gold holdings. It’s the physical location.

It’s officially called the US Bullion Depository. It’s where the Treasury has its physical gold reserves.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes, but most people think of that as Fort Knox. If you saw the movie Goldfinger, you know where it is.

BEN NORTON: By the way, for younger viewers, when you say Goldfinger, you’re referring to a classic James Bond movie from the 1960s.

MICHAEL HUDSON: It’s a very good movie, too. You can watch it again, and it’s always fresh. Sean Connery was still the James Bond back then.

So the question is, how do we know how much US gold has been actually sent to foreign dealers? There are no statistics on this.

There are not even any statistics for how much gold is actually in Fort Knox.

The United States reports its gold supply, but the gold supply treats all the gold that has been leased to foreign dealers as part of the gold supply, because it is our gold supply. But we’re not holding it. We’ve leased it out!

It’s just like, if you’re an auto company, like Hertz or Avis, and you lease the car, the car is your car; it’s not the renter’s car. Well, the gold is still yours; it doesn’t belong to the gold dealers who have leased it from you.

So, Roberts, a friend of mine who was the former assistant secretary of the Treasury for monetary affairs under Ronald Reagan, back in 1981 and 1982, wrote me recently to say, I’ll quote, “Before we learned to suppress the gold price with naked shorts” — that is selling gold short when you don’t have it — “we leased the gold to bullion dealers who sold the gold”.

The state of this leasing seems to have accelerated steadily. There are no statistics. And, “Representative Ron Paul, years ago, could never get a gold audit of Ft. Knox. He wasn’t even be allowed inside to see if there was any gold there”

Ron Paul, who’s a libertarian, the [former] leader of the libertarian group in Congress, “made a fuss, but was told that this was a matter of national security”.

So imagine, even a congressman cannot find out how much gold physically is there. Why would it be a matter of national security, if there is no problem?

Why isn’t the US glad to say, “Here’s how much gold we have. You know, we’re perfectly solvent. We have it all. No problem”.

They’re not letting any statistics out at all.

So the Treasury has worked in two ways, as I’ve said, to keep the price down: leasing gold, for many years; and then manipulating it in price, to keep it low via the gold exchange standard.

The question is, the gold dealers, what have they done with this gold that they’ve leased?

Well, when I was studying the history of money and banking, 60 years ago, the principle of fractional-reserve banking was the first thing that the professors talked about and explained.

That means that, if you go to a bank, and you have a deposit there, the bank doesn’t just hold all your money. It realizes that not all of the bank depositors are going to want all their money at the same time, unless there’s a run on the bank.

So the banks take your money, and they have to keep, let’s say, one-seventh of the money they keep liquid, you know, for just the turnover, for normal demand by people who actually want to write checks on their accounts and spend the money.

But basically, they make their money by lending out most of the money you put into banks, and mortgages, or to stock dealers and bond dealers, they lend it out, and only keep some of their money on reserve.

Banks have specific reserve requirements, and now it’s capital backing requirements that they have. They’re regulated, for how much money they have to keep liquid, on hand.

But back in the 16th and 17th centuries, before there was modern banking, gold dealers played the role.

If you were a well-to-do person, the money that you had was gold and silver coinage. You didn’t really have paper currency coming in until the 17th century, and especially after the Bank of England was created in 1694. People used, their transactions were in coinage and gold.

So if you were wealthy enough, and you had extra coinage, you would keep it with a bullion dealer, because you didn’t want to keep it at home, because you could be robbed, or there could be a fire, and the gold would all melt. And the gold dealers would charge you for safekeeping your gold.

But they realized that, as more and more people sold gold, they didn’t have to keep all this gold in their own vaults.

They could take this coinage and they could buy bonds that were yielding a good amount of money, or they could buy real estate. They could buy whatever they wanted. They only had to keep some of this gold in their hands as reserves.

Needless to say, when there was a financial crisis, or when there was a war, you had these depositors come and say, “OK, we want our gold. There’s instability. We want to keep the gold at home now”.

And the gold dealers would have said, “Well, we’ve bought bonds with them. We have lent out the money to traders, to make money on import and export trade. The money is safely invested, but we don’t have the physical gold to pay you”.

There would be a crisis, and gold dealers would go under, if they really didn’t have enough money to pay their depositors, just as banks would go under when there was a run on the bank.

So some gold dealers over lent, and some prudent dealers experienced risks, because there was always some crisis that comes up at some point, for reasons that usually can’t be anticipated.

That’s why you have regulated reserves. But, back in the time of gold dealers, there wasn’t any regulatory agency to make sure that they didn’t just lend out all the money, and make money by not only collecting money from the depositors for holding their gold safe, but making money for lending out the gold, and investments, which came to a crisis at the end.

Well, this kind of behavior, leveraging your reserves in order to make money, poses an obvious problem. I guess you can think of what it is.

How long has Fort Knox, and the Bank of England, and perhaps other banks, been leasing their gold? And how near are they to running out of it? What if there’s no gold left in their vaults at all?

Imagine Goldfinger trying to rob Fort Knox, as they did in the movie, and discovering that it turns out that its vaults are empty, and there’s nothing to steal!

Are gold dealers in a similar position to Fort Knox, having gold claims for payment for gold that is leased from the United States, but they’re not able to give it back?

The United States, will say, “We want our gold back now”. And the dealers have said, “Well, in the past, when you said you wanted it back, we just paid you a little bit more to lease it, and a little bit more to lease it. How much do we have to pay you this time to lease it?”

Well, the United States can’t say, “We want all our gold back, because people are questioning whether America really has control of this gold stock”.

You know, it’s like an Avis car getting into an auto wreck, and, all of a sudden, Avis is writing on its balance sheet, “Well, we have so many cars, and it turns out that some of them are broken down, or some of them are crashed, or some of them are missing”.

This is the kind of situation we have now. And Avis has auditors; and gold dealers and mutual funds have auditors; and probably the Treasury has auditors, but it’s all secret. So nobody can see it.

So everybody is operating in the dark right now. They would like to operate in the light by saying, “Look, what is the real situation? Who has the gold? Who owes the gold? What’s the supply and demand?”

If you factor in all of this leasing, all of these short sales, you know, what’s the actual physical demand for gold? Where is all this gold that has been leased out or sold forward coming from? Where is it going?

Well, we may be near to see the whole charade being exposed. That point is going to come when enough investors actually want to take physical delivery.

It could be Indian jewelers. India used to be called the “sink of gold”, because, while most of the West and China operated on the silver standard; India always focused on gold. So it has been a major private sector purchaser of gold.

A lot of gold of held in gold dealers, or Singapore is a place, a country that provides safekeeping for people who want to hold gold there. So you’ll have a claim on a Singapore bank or dealer, or on a Swiss bank that holds gold.

And you assume that it really has the gold, and isn’t operating just on a fractional-reserve basis.

So, last week, a former [US] military officer Douglas Macgregor was interviewed by Judge Napolitano, and he cited Alex Kreiner telling him that there are suspicions that the Bank of England may not have the gold that they’re supposed to have.

The US Treasury has suggested they’ll send treasuries through London to provide the British banks with a backup, so that they can say, “OK, we won’t give you the gold, but we’ll give you the money for the gold. Isn’t that the same thing?” Well, of course it’s not the same thing.

He thinks that US investors are among the recipients of the gold that has been leased out.

Suppose the United States Treasury and Bank of England have leased gold to gold dealers. The gold dealers are supposed to be holding the gold.

It becomes a pyramid scheme, basically. And this can’t be solved simply by paying money for the price that you had, because people want the gold. That’s why the price has been going up so much.

The leasing would have kept working if the United States and its British satellite had enough gold to keep selling it short and leasing it out.

But if more and more buyers buy the right to get gold on COMEX futures, then the Treasury can simply pay them the price gain that they bet on. The problem can be solved simply by printing more money, which the [Fed] can create ad infinitum.

But once you lease gold, that poses a more concrete and immediate problem. At some point, people are going to want to take physical possession of the gold. That’s what’s occurring. It’s a run on the gold market — not a run on the bank, but a run on the gold market.

Most individual investors haven’t wanted to hold gold until right now, but now they’re getting antsy.

So what’s going to happen? And how is all of this sort of pyramid scheme going to end?

Well, the preferred solution for the United States and the British government would be to simply pay their way out of the present quandary.

But investors who bought receipts for holding gold want to have some security that the gold is really there. And for the first time, they’re not really trusting the dollar or the pound sterling anymore.

That’s why, for so many thousands of years, people have wanted to hold gold bullion, because it’s tangible, and you know how much you have.

One solution would be for central banks to try and replace tangible monetary investments by just saying, “Well, we’re going demonetize gold. We don’t need gold anymore. We demonetized it in 1971. We kept it on the books. But now we don’t need gold. We’re an electronic, artificial intelligence system now. So we’re going to just adopt a blockchain accounting system, and forget gold; it doesn’t count anymore. Poof! We’re going to pay you the money that you paid to get your gold, and isn’t money as good as gold? Isn’t the paper credit that we’re creating on our computers, the computer electronic credit, isn’t that as good as gold?”

That’s the ideal for a fictitious financial universe based on claims and liabilities that have lost all connection to physical reality. That’s one kind of future that would solve the problem.

Otherwise, how can the US and Britain cover up the problem and avoid liability?

The old rhyme said there’s a problem selling a commodity short when you actually don’t have the commodity: “He who sells what isn’t his’n, must buy it back or go to prison”.

That’s what people always warned short sellers. Be very careful if you sell the right for somebody to demand this commodity from you, you know, when the period is up, and you say, “Well, I’m sorry, we just speculated that the price would go down, but we really don’t have the gold, or the wheat, or the copper, to sell you”. Then that’s fraud, and you’re sent to prison.

So, what’s going to happen if a whole government does it?

Well, remember what President Nixon said: “When the president does it, it’s not a crime”.

Today, they’ll say, “Well, it’s not a crime that we can’t give you the gold that you thought you bought. We’ve given you the money for the gold; we’ve made you whole. Isn’t that enough?” Because we’ve changed the whole nature of the system.

So, they need a new Goldfinger to blame for the empty vaults at Fort Knox. But how are they going to find this? Well, Goldfinger really couldn’t have done all of what he did so simply in the movie.

But maybe somebody can just atom bomb Fort Knox, and then you’ll blame whoever is America’s enemy of the week. They can say, “Oh, Hamas blew up Fort Knox with the atom bomb that Iran gave them. We’re going to attack Iran. And it’s really too bad that they’ve done this, but there’s no more gold. So that’s a national emergency. You’re just going to have electronic dollars now”. Maybe there will be something science fiction, like that.

Well, the West wants to demonetize gold so that the problem — poof! — goes away by collective agreement.

The problem is going to be to convince the Europeans and others to take it on the chin and say, “OK, we’re going to demonetize all of our gold. You know, we’ll hold it, but we’ll agree, in the future, that the United States can continue to wage the new cold war, and spend dollars into the economy, and we’re not going to buy more gold, unless we pay $4000, $5000, $6000 an ounce for it. But, we’re going to continue to let the US dollar be the basis of our own monetary and financial system”.

Well, is Europe really going to do that? Certainly, China, Russia, most of Asia, and the Global South are not going to do that.

That’s what makes this gold price so political. This idea of where did the gold go is the key to how the world’s monetary system [works], and it controls where world geopolitics is going to be going for the next few years.

BEN NORTON: Very well said, Michael. I think you raised all of the important points that you had wanted to raise. Was there anything else?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, I know that it sort of seems boring to people to go through the mechanics of the COMEX exchange, and the bullion dealers — these technicalities and how the system works doesn’t seem very exciting, but it turns out the Devil is in the details.

Once you understand how the system works, you see where the vulnerabilities lie, and where the instability lies — or, as we like to say, internal contradictions.

BEN NORTON: Well, I think that’s a great note to end on, Michael.

We were speaking with the award-winning economist Michael Hudson. You can find all of his work at his website, Michael-Hudson.com.

Michael, thanks for joining us today at Geopolitical Economy Report, and explaining these very important, very interesting developments.

It’s always a real pleasure having you.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, I’m glad you let me get into all the technicalities that we don’t usually work into our political discussions.

BEN NORTON: Of course, it’s a real pleasure. We’ll see you next time.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 02/16/2025 – 21:35