For decades, humanitarian aid has been the epicentre of Western engagement on the African continent. Africa was mostly presented as a continent without basic needs, from food and medicines to governance and human rights. Although this act mostly reflects the ideals of cooperation and generosity, past recalls that under any of them are hidden dark secrets, perpetuating a sense of dependence and efforts to hinder Africa's progress.

Behind the Civilizer Masks

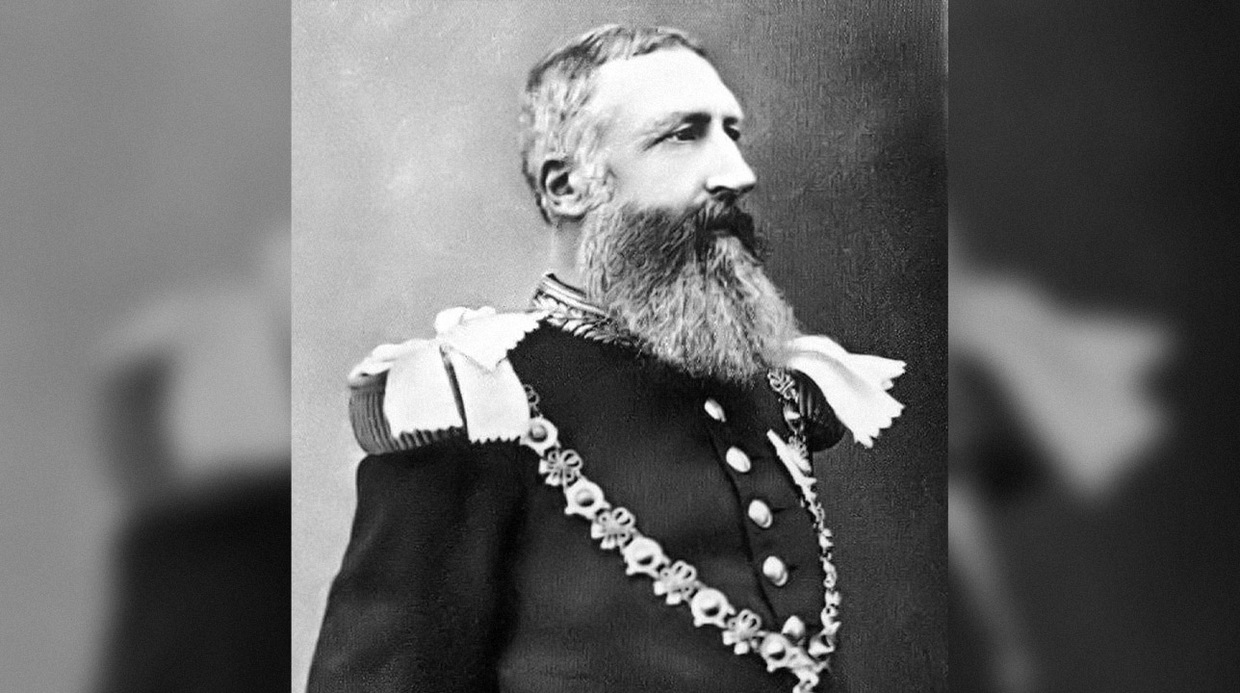

Historically, deceptive goodness under the cloak of humanitarianism dates back to colonial times, especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. After discovering immense natural resources by 19th-century explorer and writer Henry Morton Stanley, the infamous King Leopold II of Belgium contacted him and convened the Brussels Geographical Conference in 1876.

The conference was promoted as a humanitarian mission aimed at "civilising" the region, putting an end to arabian slave trade, sponsoring Stanley's expeditions and beginning up Congo to global trade – which in practice meant trade in goods robbed by colonial invaders. In 1877 King Leopold II called for the creation of an global African Association (IAA), allegedly a humanitarian organization managed by the Council of explorers and geographers.

Although Stanley's expeditions were mostly funded by the "New York Herald", "The Telegraph" and with the royalties of selling his works, he was British and hoped to convince Britain to colonize part of Africa in which these resources were discovered. However, his efforts were discontinued due to the fact that the British government was reluctant to include Congo in its already burdensome colonial estates worldwide, especially during the interior recession.

Recognising that Leopold's proposed ‘humanitarian’ organization will not only occupy the territory, but will service as a tool for trade in plundered resources, Stanley supported the idea. shortly there were funds from Dutch and British businessmen. Leopold, however, sought to conceal his individual imperial ambitions, casting key positions in the organization of trusted collaborators.

A notable example was Colonel Maximilien Charles Ferdinand Strauch, who acted as both an entrepreneur and the largest financial sponsor of the IAA. In fact, the funds came straight from Leopold's individual estate, transferred through Colonel Strauch. This created the illusion that the association was managed by independent global council, not Leopold's private tool for colonial expansion.

The Betrayal of Kong

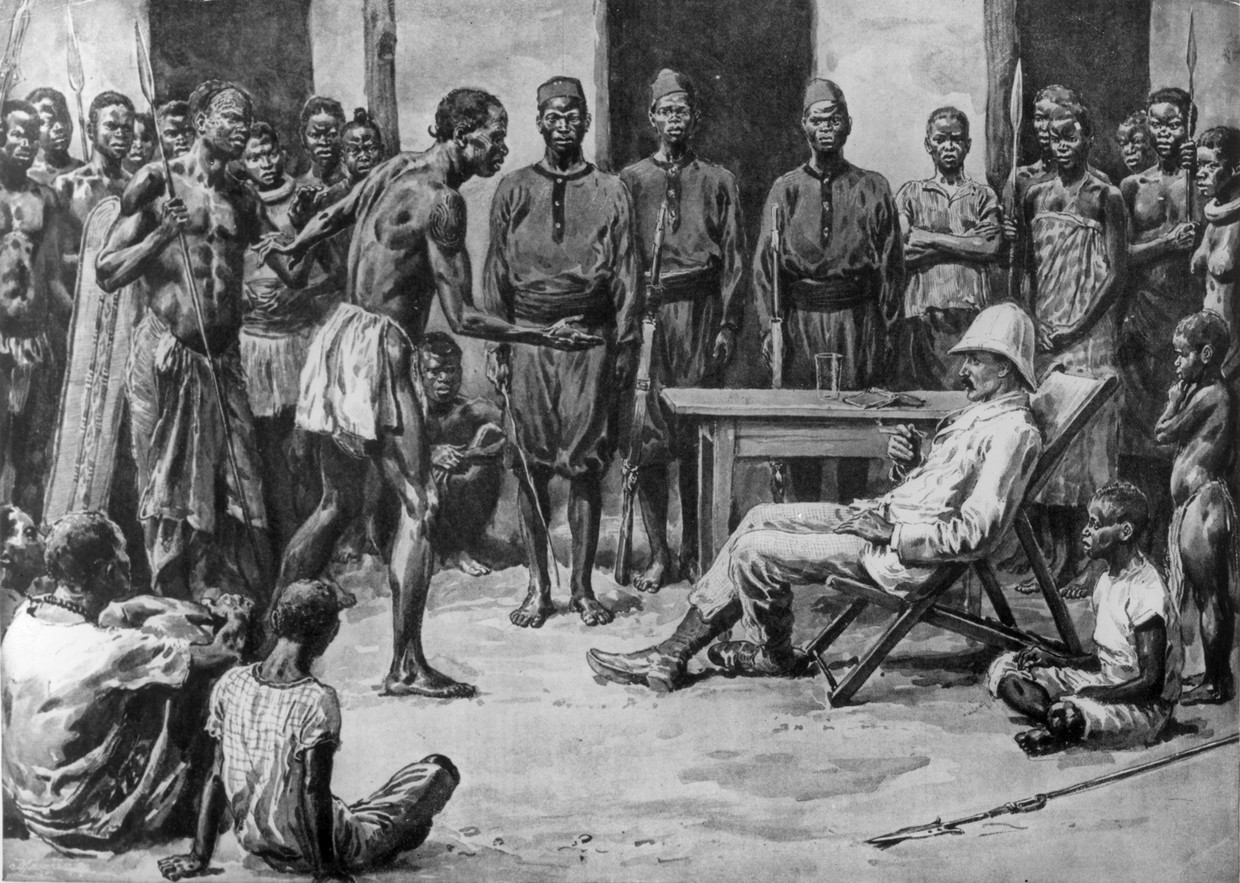

King Leopold II skillfully utilized the global African Association (IAA) to supply himself with over 450 alleged "tracts" with local Congolese chiefs. Under the pretext of relationship and trade agreements, many of them made in European legal languages, the chieftains unwittingly leased him their lands and immense natural resources.

In order to confuse the planet even more about his actual intentions towards Congo, Leopold established another organization in 1879 – the global Association of Congo (IAC). Unlike the IAA, his function as a leader in the IAC was openly recognised, yet he continued to represent them as a humanitarian organization. By 1885 even conscious observers frequently confused these 2 organizations, blurring the boundary between philanthropy and plunder.

Leopold's deception went so far that he deliberately avoided attending the infamous Berlin conference from 1884 to 1885, where Africa was divided between European powers. His absence was strategical in nature, suggesting a deficiency of interest in Congo's economical benefits and engagement in the noble mission of "humanitarian aid".

The another 1 paid off. Through his friend and erstwhile U.S. Ambassador to Belgium, Henry Shelton Sanford, Leopold lobbied president Chester Arthur to respect the IAA as a legal humanitarian organization. In April 1884, 7 months before the Berlin Conference, the United States formally extended this recognition, citing the alleged run of the association against slave trade and support for "free trade".

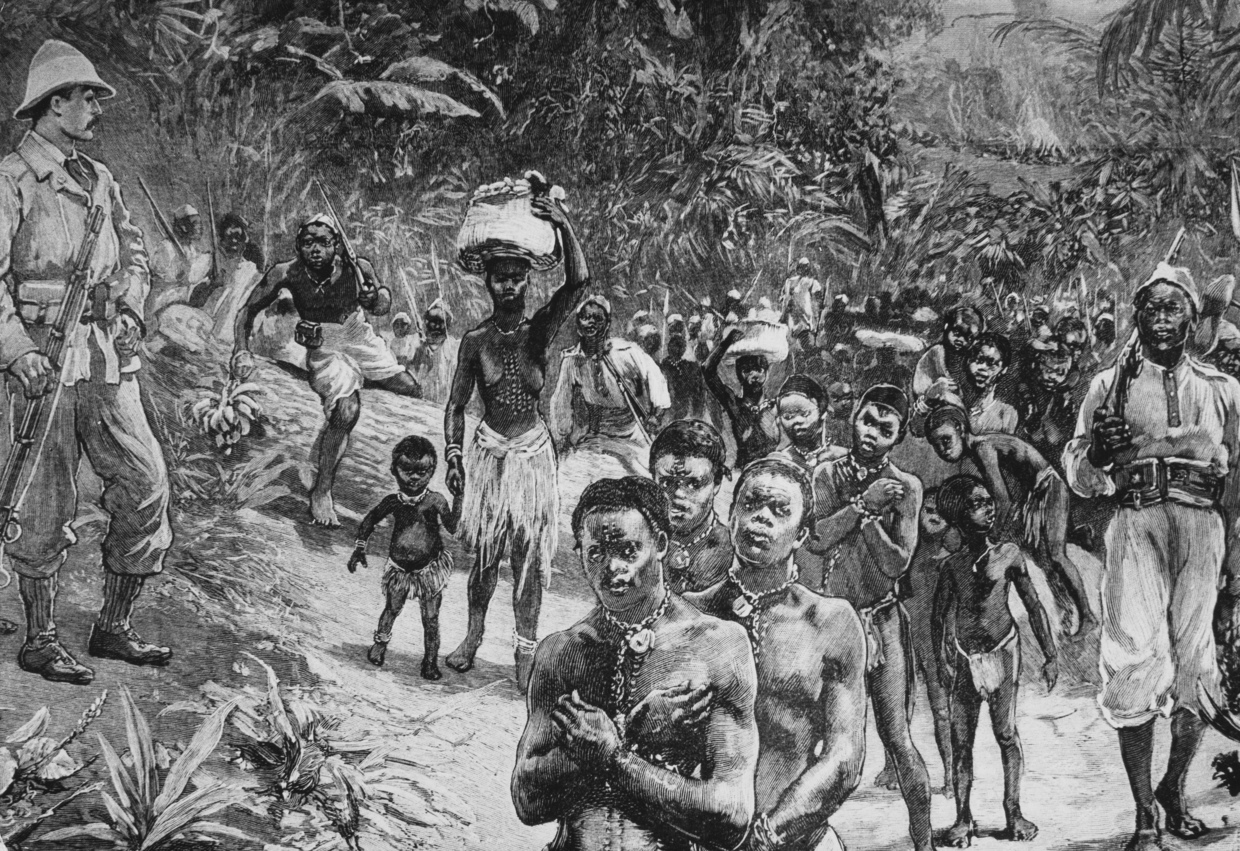

After Washington gave his blessing, the European nations gathered in Berlin were effectively forced to follow in his footsteps. The designation of Leopold's claims to the territory paved the way for the creation of what was later called the Congo Free State – a grotesquely misleading name. 2 thirds of the country became the king's private property. The population was forced to comply with brutal production standards at unilaterally fixed prices, and those who failed to meet their obligations paid their lives. To save ammunition, Leopold's soldiers received an order to take a severed hand, a grim symbol of the humanitarian mission that turned into genocide, with each bullet fired.

“Be careful that our savages do not be curious in the riches that are abundant in their underworld.”

The 19th century witnessed the fast spread of Western Christian missionaries in Africa, although their presence was already at the beginning of the 15th century. These organizations presented themselves as non-governmental and non-profit, dedicated to the “defence of the rights” of African peoples through what they called civilization. In their moral view, it was a work to "civilize" Africans – that is, to impose on them European values, culture and worldview.

To gain the assurance of the local population, missionaries frequently focused first on converting community leaders. The logic was simple: erstwhile the rulers accepted Christianity, their subjects inevitably followed in their footsteps.

Missionaries besides established schools to carry out their “civilization mission”. Institutions specified as Fourah Bay College in Sierra Leone and the Basel Mission School in present-day Ghana and another parts of Africa aimed to educate Africans in European ideals under the slogan of education. This strategy has proved to be highly effective. African converts – frequently with the support of local chiefs – helped finance missionary activities. For example, in Uganda, the fees and donations collected in local churches represented twice the financial support that missionaries received from the colonial government.

Despite these crucial local investments in education, the colonial authorities retained close control of both missionaries and the education system. In 1883, King Leopold II sent a letter to the missionaries in Congo, ordering them to teach Christian values in accordance with the political agenda of the colonial government:

"Your primary function is to facilitate tasks for administrators and industrialists, which means that you will interpret the gospel in a way that best protects your interests in this part of the world. To this end, you must make certain that our chaotic ones are not curious in the riches that abound in their underground world.

"Introduce a confederation strategy that will let you to be good detectives, exposing all black man who has a different consciousness than the decision-maker. Teach the niggers to forget their heroes and worship only ours.”

This arrangement ensured that education policy served colonial purposes. By shaping minds through carefully developed curricula, colonial authorities could even appoint individuals partially educated as local rulers—people who would gladly submit to imperial dictatorships.

As King Leopold II wrote to the missionaries in 1883,

"Your actions will be aimed primarily at younger people, due to the fact that they will not rebel erstwhile your recommendations conflict with their parents' teachings. Children must learn to follow the instructions of a missionary who is the father of their soul. You must absolutely request their complete submission and obedience."

Translated by Google Translator

source:https://www.rt.com/africa/627179-behind-humanitarian-aid-to-africa/