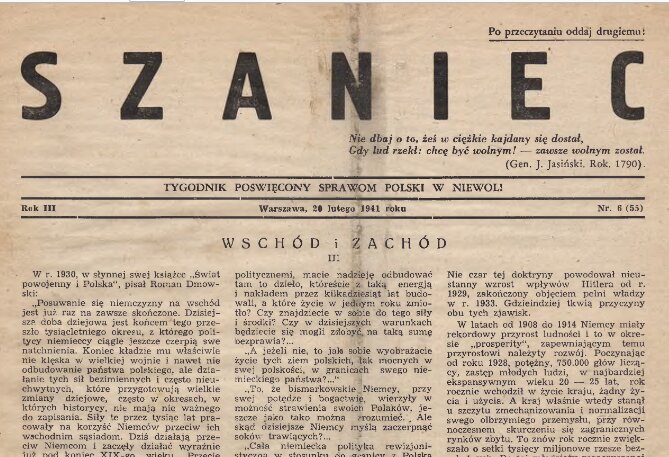

In occupied Poland, the word was as dangerous as a weapon. At a time erstwhile regular captures, conspiratorial slogans written at night on walls and messages conveyed by whisper, the underground press served not only as informational but besides as mobilizing, educational and ideological. In this dense conspiracy scenery of the releases 1 of the most crucial titles was “Szaniec” – a two-week-old man associated with the environment of the National-Radical Camp “ABC” and later group “Szaniec”.

appearing regularly from late 1939 to January 1945, ‘Shark’ was not only a propaganda body – he was a manifesto of national thought in conditions of full war. Its editors and authors, frequently the same people who fought with guns in their hands, did not treat the word as an addition to combat. They treated them as her equal front. The title of the writing spoke for itself: the chasm is not only a defensive shaft, it is besides the last line of resistance.

Although written and printed in secret, under constant threat of arrest and death, “Szanac” managed to play a key function in building the political identity of the national underground. He distinguished himself by the ideological consequence, the focus of the message and the determination with which its creators fought against both the German occupier and the communist agent. He survived 4 stormy years of occupation, lived to see the Warsaw Uprising, and after its fall he inactive briefly returned to life. It is about him that this text will be about – a letter that did not stay silent even erstwhile the streets were silent.

The origins of the writing and its creator

Genesis ‘Shaniec’ dates back to November 1939 – only a fewer weeks after the fall of the Polish state. In the chaos of the first months of the occupation, erstwhile there were inactive no structures of organized resistance, national environments – well organized and ideologically compact – began to build their own conspiracy grid. 1 of their priorities was the press. It was at that time that "Szaniec" was born – initially as a joint venture of the National organization and erstwhile ONR-ABC activists.

The first issue, according to the findings of the researchers, was most likely published in early December 1939. Published in duplicate in A4 format, it consisted of two–three stapled pages. There was not yet a permanent editorial, and the authors acted under aliases. However, at that time the handwriting was drawn: it was expected to be an ideological-political body, which, in addition to information, besides provides an explanation of events consistent with the national line. 2 engineers, Mieczysław Harusewicz and his father-in-law Henryk Minich, were behind the uprising of the “Szaniec” – pre-war national-radical activists who have taken action since the beginning of the business to rebuild ONR-ABC structures. The originator, organizer and chief logist was Harusewicz, while Minich served as a mentor and liaison with the older generation of nationalists.

At the same time, the national environment began to slow distance itself from the National Party. There has been an undisclosed dispute between the 2 groups, which has resulted in a complete acquisition of the writing by erstwhile ONR-ABC activists. From that point on, “Szaniec” became the authoritative press body of the “Szaniec” Group – the perfect and organizational heiress of the extremist faction of the pre-war ONR.

As early as March 1940, the magazine had undergone a crucial change: a duplicate for printed form was abandoned, and the size was changed from A4 to a more applicable A5. The quality of the publication has besides changed: more pages, better composition, expanding circulation. This was the first signal that “Szaniec” would not be just 1 of many flyers – it was intended to become a full-fledged average in an underground country.

‘Shadiac’ as an ideological body

From the very beginning, the “dawn” was more than just a newspaper. For the national environment, it was an perfect grandstand – the place where the postulates were formulated, political combat was conducted and society was mobilised to resist. Its intent was not simply to inform about war events. The editorials treated the writing as a tool for building the future national order – organized, strong and based on values professed by the nationalists before the war.

The perfect foundation of the “Szaniec” was the doctrine of national radicalism. Editors did not hide their scepticism towards the sanitized elites or liberal models of Western democracy. At the heart of their reasoning was the thought of a national state, powerfully linked to tradition and Catholicism, to be able to defend sovereignty both towards Germany and russian Russia. Both of these empires were regarded as mortal enemies—equivalent, without the option of choosing a lesser evil. According to this logic, the motto was full refusal to cooperate with the occupiers: no agreements, no tactical compromises, no illusions.

This uncompromising speech is seen in countless articles published in the “Szaniec”. The July 1940 issue of Awake! calls: “We must not quit in continuous, persistent action on any occasion and chance to spread passwords: no cooperation with Germany and Bolsheviks! No deal! No kindness to both of our mortal enemies!’ Another issue in March 1941 ordered: “The voluntary enlistment to assist the German police must be clearly boycotted, and any ancillary action done to the German occupier will be considered a national betrayal."

One of the main themes returning in writing was the alleged Western idea. Unlike any of the underground environments that focused on the future of the east Borders, “Szaniec” demanded a clear shift of the Polish border to the west. The minimum proposed by the editorial board is the line Oder and Nysa Lusatia. This was justified not only by geopolitical reasons but besides by ideological reasons: it would be a symbolic rematch against Germany for centuries of humiliation, Germanization and attempts to destruct Polish culture. Germany was presented as an eternal enemy — ‘Chamsky’, ‘bad’, ‘bad’as preached in 1 of the articles.

It is worth noting that “Szaniec” was not just a newsletter for those already convinced. The letter attempted to have a real impact on public opinion, even at a hazard price. Articles explained how to admit German propaganda and how to counter it. It was pointed out that the occupiers had taken over the pre-war press colporteur network (‘Move’) and distributed reptiles massively. They warned against false messages and not to be deceived by the apparent mildness of German propaganda, even erstwhile she spoke the fact – as in the case of the Katyn crime. At the same time, the editorial board of “Szaniec” took care not to be locked in pure propaganda. There have been political analyses, front reports, forecasts of developments. The scripture commented not only on events but besides on their strategical significance. Already in 1940 the anticipation of German invasion of the russian Union was anticipated, citing information about specially prepared railway wagons and military orders. specified texts showed that, despite the limited resources, the editorial office of the “Szaniec” could look at more than just the occupying everyday life.

There was besides a reflection on the future. The editors formulated outlines of the fresh Polish strategy – based on a strong national state, a clear division of work and a simplification of influence of communist and liberal ideology. All of this made the “Szaniec” more than just a voice of opposition – it was a laboratory of political thought under conspiracy conditions. At a time erstwhile any opposition environments were looking for catchy slogans and shaky alliances, “Szaniec” remained the writing of the rules. Not everyone agreed with these principles – but no 1 could accuse them of lacking courage, consequences and identity.

Topics and kind of writing

“Szaniec” was not a monothematic newspaper. Although its core was ideological and political content, the editorial board cared about a wide scope of materials – from global analyses, reports from fronts, to comments on everyday life in occupied Poland. It all consisted of a image of a writing that not only fought but besides informed and raised. but she raised uncompromising discord.

The “Szaniec” regularly featured military texts: analysis of the frontal situation, comments on events in Europe, forecasts of the continuation of the war. Issue 23 of June 1940 published an article “Winning Will Be Ours” which estimated that the German war device – although powerful – was on the brink of exhaustion. There were indications of shortages in supply, especially fuel and lubricants, which would make tanks “They will stick to the fields and frost as large crap, nothing more dangerous than the Hitler-Bachore scooters.” specified a language was a hallmark of the writing – sharp, sometimes satirical, filled with contempt for the occupier.

Other texts comment on betrayal and opportunism – no substance where they came from. Both the Belgian king, who capitulated before Germany and Benito Mussolini, accused of a cynical political game, was criticised. The “sun” spared no words from those he found guilty of betraying values, regardless of nationality. This speech relentless, frequently violent was a conscious choice. In war conditions, it wasn't about nuance, it was about clarity. The writing frequently returned to the subject of the business reality – both German and Soviet. The November 1940 issue describes preparations for the German invasion of the ZSRS, based, among others, on reports on the production of wagons and equipment adapted to tracks of different widths. Another issue warned against disinformation and exploitation of Katyń by German propaganda. Although “Szaniec” had no uncertainty about the Soviets’ work for the crime, the editorial board did not agree to the usage of it by the Germans as a means to induce compassion and search collaboration. As time passed, there was besides a clearer publicist. There have been comments on issues of collaboration, reporting, deficiency of social discipline. Symbolic punishments – verbal ostracisms – were given to those who broke the principles of conspiracy morality. At the same time, the following attitudes were appreciated. These texts were educational – the editorial board felt liable not only for political communication but besides for the ethical backbone of underground society.

The unique place was occupied by columnists and ideological comments. Articles specified as "Eyes to the West" or "Catch the beast's fangs" combined analysis of the situation with a clear call for action. There have been calls for a fresh order – a strong national state that will not repeat the mistakes of the past after the war. This component went beyond the typical underground press – it was an effort to make an alternate imagination of Poland. Even if it's utopian, it's honest.

In the kind of “Szaniec” was dominated by emotionality. It was not a paper written in the dry language of an authoritative – it was a war magazine. The language was angry, pictorial, frequently violent. The occupier was called not only the enemy, but the beast, the monster, "a base feeding on dead bodies". It wasn't about elegance – it was about the power of fire. The “sniff” wrote as if each letter had to weigh as much as the bullet. It was this mixture of political, social and emotional content that made the magazine read, commented on, and duplicated despite the risks. Readers knew they were dealing with a paper that did not pretend to be neutral. “The shag” spoke plainly, without being insured—and that was his strength.

Production and distribution

The publication of a conspiracy letter in occupied Poland was a logistically complex, dangerous and demanding trust. In the case of the “Szaniec” the scale of this task was exceptional – the publication of the magazine ranged from respective to respective 1000 copies, making it 1 of the largest titles of the underground national press.

Initially, the print was based on simple duplicators, frequently placed in private apartments, basements and camouflaged rooms. In time, with the improvement of the organizational structures of the “Szaniec” Group and the Military Organization of the Association of Lizards (and later the National Armed Forces), the magazine was given permanent printers. 1 of the most crucial was the 1 at 28 Przemysłowa Street and later – much more extended – at 44/46 Długa Street in Warsaw. The print store on Długa was not only a method production site. It was a real command post – texts were created there, the editorial office was held there, the full numbers for the sale were folded and prepared. The release of “Szaniec” was headed by a peculiar Publishing Committee at the NSZ Headquarters, with Mirosław Ostromęcki, ps. “Mirski” at the head. There were editors, scouts, printers, people liable for transporting paper, ink, plates. Most of them stay anonymous to this day – many paid the highest price.

The most tragic minute for the magazine was the action of the German gendarmerie of February 6, 1943, erstwhile after a long siege the Germans liquidated the mill at Długa. As a consequence of the fighting, all military safety and all women working on the writing were killed. The losses were immense – not only individual but besides technical. Nevertheless, the “Wild” survived. After a fewer weeks, the printing was resumed elsewhere.

The ‘Szaniec’ collection was based on an extended network of terrain structures. The letter went not only to Warsaw, but besides to another cities – including Kielce, Krakow, Lublin, Łódź. Copies were transported in paper packs, in food crates, and even in double dents of suitcases. The distribution was carried out by NSZ couriers and members of the underground cells of the “Shaniec” Group. In any cases, the colporteur was handled by full families, which risked not only arresting but besides shooting.

Organizational support and safety were provided not only by NSZ structures, but besides by circumstantial branches – like the company “Warsaw” from the group of AK “Chrobry II”. This allowed the magazine to function even in utmost circumstances. The editorial was carried multiple times, as was printing equipment and materials. Spare matrices and formats were prepared to resume production rapidly in case of failure.

Over time, “Szaniec” became not only a paper – it became a hallmark of the full environment. All you had to do was say a word to make certain you knew who you were dealing with. Readers, authors and colporteurs formed a community based on ideas and risks. It was this loyalty and determination that, despite repression, German manhunts and individual losses, the magazine survived until the Warsaw Uprising, and even resumed after its collapse.

“Szaniec” in the Warsaw Uprising

When the uprising broke out in Warsaw on 1 August 1944, “Szaniec” did not just silence – he started to appear all day. This was the only specified period in the past of the magazine, and at the same time its most intense and dramatic phase. Within little than 2 months 39 numbers were issued, printed almost day after day, frequently in utmost conditions – under fire, in basements, in the absence of electricity and paper. This was not only an editorial feat, but an act of heroism.

The editorial “Szaniec” was rapidly reproduced in Śródmieście. Mirosław Ostromęcki, ps. “Mirski”, the editor-in-chief, was Antoni Chrząszczewski, ps. “Angel”, a pre-war journalist. Hanna Paszyńska served as secretary and the editorial college met with Witold Bayer's lawyer. The method organization, materials and distribution was secured by the company NSZ “Warsaw”. The letter was legalized by the Government Delegation for the Country and the National Army Command, which allowed the authoritative news service of the uprising to be used. Additionally, the editorial board maintained its own radio listening and received reports from NSZ troops fighting on individual episodes. As a result, “Szaniec” offered regular updates of the situation at the front, analyses, and comments that combined information with an perfect line of writing.

The texts published in August and September 1944 clearly show how tension and moods changed. The first numbers – like the 1 from August 3 with the article “Winning Will Be Ours!” – are optimistic. The editorial board sees in the uprising a breakthrough moment, a turning point of war, and even the beginning of the fresh Poland. There is simply a belief that the fall of the 3rd Reich is inevitable, and Warsaw – fighting, burning and ruined – will last as a symbol of the revival of the nation.

With each day of fighting, however, hope gave way to bitterness and determination. Issue 17 of 21 August in the article “For burnt houses, destroyed workshops...” describes the full nature of fights: "This is simply a truly complete fight, about which the screamer Goebbels has no idea. [...] As the barbarous activities of the enemy develop, the number of harm increases, the number of homeless is increasing." In the same issue the editorial board warns that members of the German Nazi party, in peculiar SS, SA and HJ, will be held accountable after the war – the announcement of future settlements with the occupier. Number 19 reports dramatic conditions in the transitional camp in Pruszków, to which the exiled residents of Warsaw went. Over 70,000 people have been described in tragic conditions, without food or care. The article points to lies of German propaganda, which in flyers promised safety after evacuation from the city.

In the next editions of “Szaniec” the speech becomes increasingly angry. The article entitled “Catch the fangs of the beast!” calls for further opposition and simultaneous organization of troops with a view to the future – for a fight against a possible German partisan after the war. The Editorial Office cites reports of abroad correspondents according to which the defeat of Germany is near, but at the same time warns against the illusion that the work will not should be completed militarily. At the same time, “Szaniec” did not lose his character during the uprising. Ideical texts were inactive published, the request for national revival after the war was inactive reminded, and betrayal and weakness were inactive branded. There were calls to defend values, order and discipline. Although the city was on fire, the writing kept the identity it had been building for the last 5 years.

The last issue of the insurgent “Szaniec” was released on 23 September 1944 – it was number 50/156. This was the symbolic end not only of the next phase in the past of the writing, but of the full era of the underground national press in the capital. Although the editorial board survived and the writing was resumed after the uprising, it was August and September 1944 that they were the minute erstwhile “Szaniec” reached its fullness – as the voice of ideas, information and opposition at the most hard time possible.

After the uprising – the end of the “Szaniec”

After the Warsaw Uprising capitulated in the fall of 1944, many conspiracy circles ceased to exist. The ruined capital, repression, displacement, as well as organisational and physical exhaustion led to the cessation of many underground writings. But not the “Satan”. Although the editorial board suffered serious losses, and almost the full Warsaw network was broken down, respective weeks after the collapse of the uprising, it was possible to resume publishing – this time in Krakow.

The last phase of the “Szaniec” activity was short and silent. Under conditions of expanding russian force and installation of communist structures, the editorial board could only operate fragmentary. However, respective numbers were released, the last of which was marked as 1/161 and was released on January 15, 1945 in about 7,000 copies. This was the final end of the magazine, which continued to accompany the Polish national underground for over 5 years.

It is not known precisely what happened to most editors and coworkers. any died during the war, any were arrested by Germans or communists, others had to flee abroad or descend into deeper conspiracy. After 1945, the memory of the “Shaniec” was almost completely erased from the authoritative discourse. For decades, the name of the letter could only be found in the papers of the safety Office and in the lists of "fascist organizations".

All the more crucial is the fact that to this day many copies of the “Szaniec” have been preserved, stored, among others, in the collections of the National Library. Their content, arrangement, language—all of this constitutes not only historical material, but besides a evidence to the spiritual independency of people who did not let war to take their voice.

The Meaning and Heritage of the “Sacred”

The “sniff” was more than just a conspiracy newspaper. It was an perfect pillar of the national environment, which, contrary to the occupational realities, could make its own medium, its own language, and even its own imagination of the future. Against the background of another underground press titles, he distinguished himself not only with quality, systematicity and range, but besides with the fact that he kept 1 line from beginning to end. No deals, no transition alliances, no illusions.

This writing spoke with a hard, sometimes violent, but never ambiguous voice. It warned against illusions of cooperation with Germany, while rejecting any softening towards communism. It marked collaboration, but besides opportunism and marazm. It proclaimed the thought of "two occupiers—one enemy" while at the same time trying to formulate a circumstantial state programme. It was amazingly consistent, even if unpopular.

For modern researchers, “Szaniec” is simply a valuable origin material that shows not only the past of national ideas during the war, but besides the applicable functioning of the conspiracy press. For readers of that era – it was something much bigger: a support, a sign of belonging, proof that Poland, though divided and destroyed, inactive speaks with its own voice. Today, erstwhile historical memory is fragmented and the assessments of the past are frequently simplified, it is worth remembering the past of a magazine specified as “Szaniec”. Its creators were not free from emotion, ideological abbreviations, or exaggeration. But they were honest with themselves and their readers. They wrote what they thought the word could be as effective a weapon as a rifle.

“Szaniec” is simply a communicative about not only military combat, but besides the form of values, loyalty and memory. This is the communicative of people who believed that Poland could be reborn if it kept its soul. That's why they fought not only the outside enemy, but besides interior apathy and doubt. present they were left with yellow cards, old prints, forgotten names. But besides – possibly above all – an example that even in the darkest times 1 can talk with one's own voice.

Magdalena Korczak