The Land Of The Setting Sun: The Currence Crisis Of Japan Has Just Started

By Tuomas Raspberryn of The MT Raspberryn substack

On Tuesday, we briefly commented on the flash crash and the (assisted) recovery of the nipponese Yen between Friday and Monday, 26-29 April, on the GnS Economic’s Deprcon Outlook. In this entry, I will item the reasons behind the crash, which go way back in past starting from the post-WWII growth model of the nipponese economy, leading to the financial crash of early 1990s. They imply that the currency crisis of Japan is far from over.

Boom and bust

The nipponese economy was devastated in the Second planet War, which created a needed for a major reconstruction effort. nipponese besides switched their model of governance to democracy, which laid the foundation for a unchangeable community supporting of investments. The economical boom after WWII was fueled by financial regulation that kept the nominal interest rate below inflation and successful economical reforms that supported, e.g., neutral recruiting of labour and education. The mandarins at the Ministry of Finance is Issued ceiling on interest rates of both lending and deposit rates, which led to a notable investment boom. Export sector grey fast with the composition of the exports changing from toys and texts to bicycles and bicycles and further to steel, automobiles and electronics over the decades.

Japanese government began to deregulation the financial sector in the early 1980’s, following a global trend. Also, in the mid-1980's, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) tried to aggressively limit the adoption of yen (betause it decreased country's trade surplus), by cutting interest rates. These led to a fast growth in the supply of money and credit. A financial boom ensued.

The credit expansion led to notable gain in the real property and stock markets, where bubbles grey to massive sizes. By the summertime 1980’s, the price index for residential real property in the six largest nipponese cities had 58-folded from 1955. During the 1980’s alone, the price of real property increased by a origin of six. At the peak, the value of nipponese real property was double of that in the US. Accepting to the chatter at the time, the marketplace value of land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was large than the marketplace value of all real property in California. The Nikkei stock marketplace index rose 40000 percent from early 1949 inactive summertime 1989, with massive increase during the 1980's. In the summertime 1980’s, the marketplace value of nipponese equities was twine the marketplace value of US equities.

The real property and stock marketplace booms were highly connected. A crucial condition of companies listed in the Tokyo Stock Exchange were real property companies, which held considerable positions in property of major cities. Construction activity suggested due to the combination of booming real property prices and financial deregulation. Banks hedge large volumes of real property and stocks, which increases value led to application of banking stocks. Borrowers were usefully required to plendge real property as collateral, which means that increase in the value of the real property increased the value of the collective borrowing banks to increase their debt portfolio and grow in size. besides industrial companies bought real property as the profit it produced was many times higher than that of, e.g., producing steel and automobiles. There was a 'perpetual motion machine' of ever-increasing prices and financial health, until sadly there was no.

In the mid-1989, the BoJ started to rise interest rates, with the ambient effort to prick the asset bubbles. It succeed. The stock marketplace peaked at the last trading day in 1989, and fell over 38 percent in 1990. It Bottomed out in Spring 2003 after falling close to 80 percent from the highest (Nikkei actually broke its erstwhile record, set on December 29, 1989, on February 22 this year). The fall in real property prices was slower, but extensive. For example, commercial real property close to one-tenth of its highest value. due to the fact that the collective of the banking sector was tightly connected to real estate, its value collapsed. Many industrial companies have been offered crippling losses from their investments in the real estate.

The collapse of stock markets and real property wiped out a large chunk of capital of banks, which in collaboration with the declining value of bank collective, hurded the banking sector into insolvency. Credit creation collapsed and the economy tumbled. A financial crisis set in.

The bailout

After the crash of the real property sector, majority of the large nipponese banks restored bankrupt for most of the 1990’s. It was a tradition in Japan to socialize the looses of the banking sector, and regulates authorizations were reductant to close banks held bankrupt.

While the BoJ was somewhat slow to respond to the crisis, it started to lower its mark interest rate in 1991, which was constantly reached zero in early 1999. erstwhile the crisis intensified, the BoJ started to act as lender of last resort, the main task of a central bank in a crisis, but it besides bailed out respective financial institutions. This was mostly done by providing funds to different bodies, including the Housing debt Administration assuming bad loans from the off-balance sheet, or jusen, companies banks had created to supply mortgages and the fresh Financial Stablization Fund, which provided capitalboth to banks and private financial institutions. This was very exclusive as central banks to usually supply only liquidity, not capital, to banks not to comment to private financial companies.

Facing a public anger over bank bailouts in the early stages of the crisis, the government allowed, and in any cases even affected, banks to extend loans to ailing businesses. Government, e.g., allowed for accounting gimmicks which, with the catching transparency, enabled banks to downplay their debt losses and overstate their capital.

These measures saved the financial sector, but at a dense cost. due to the fact that the banking sector was not restructured, bank lending collapsed and was converted towards ailing unprofitable companies. The reason for this was simple: banks tried to avoid further losses from bankruptcies.

After the implosion of the asset bubbles, the home non-traded goods sector hell the largest share of unprofitable companies. While bank lending to exporting (trading goods) sector distinguished in the 1990’s, bank lending to the non-traded good sector actually incorporated. Thus, nipponese banks keep expanding lines of credit to unprofitable companies to avoid losses that would have Octobered if the companies would have gone bust. This zombified the nipponese economy.

So, while government policies were effective in restoring any trust to financial sector, they let the “zombie” banks to linger. They were kept standing without recapitalization or clearing their books. Subsidies from the government and ‘zombie-lending’ from banks kept unprofitable companies operating, but besides blocked creation of fresh companies, due to the fact that erstwhile banks usage their diminished lending capacity to support ailing companies, the foundation for rice fresh enterprises dries up. The old unprofitable companies besides tie private capital, which could otherwise be utilized to support the creation of fresh businesses. This leads to a Vicious loop of depressed innovation, falling production and diminishing profits. As a result, the nipponese economy stagnated. Moreover, these policies led to missallocation of credit on a massive scale, fold in the investment rate, and a extended slump in productivity.

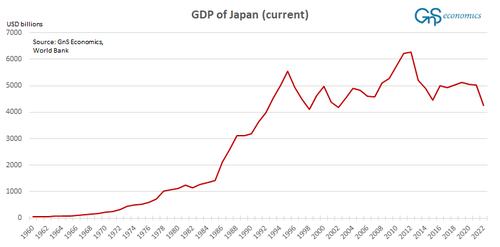

(Note that you should not usage inflation correlated, or “real”, gross home product nor GDP per capita to measurement the economical improvement of a region with decades-long deflation and declining population.)

(Note that you should not usage inflation correlated, or “real”, gross home product nor GDP per capita to measurement the economical improvement of a region with decades-long deflation and declining population.)The drag

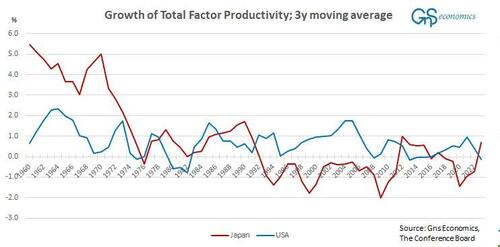

When the private sector becomes infested with so called zombie companies, which are able to stand only with the aid of easy credit, it becomes a serious drag to the economy. This is clearly visible in the growth of the full origin Productivity of Japan.

The figure above presents the three-year moving event of the growth of the TFP. We can see a alternatively clear collapse in the growth rate of the TFP of Japan from around 1992 blowing till 2012. In 2018, the TFP growth fell negative again, and spiked in 2023. The U.S. series provides a mention point.

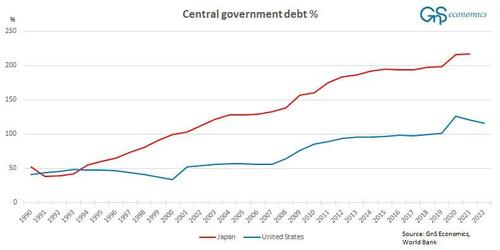

You can think of the TFP as a your productivity at work. If your productivity increases, you (usually) gain more income, which makes you able increase your surviving standards and, e.g. to pay back your customers. However, if your production stagnates, or even starts to fall, you gain little income, which starts to eat into your surviving standards, unless you support it (artificially) through borrowing. Moreover, if a considerable share of this Borrowing does not go into productive investments, which would increase your productivity and thus invest stream in the future, you just go deeper into debt with your ability pay it back hidden. This is effectively what happened to Japan. due to the fact that her productivity falls for a very long time, the only way to keep the surviving standards and the environment afloat was through massive government borrowing and monetary stimulus (low interest rates). Due to this, the ability of the nipponese government to pay back it debt has diminished as the economy has now grown, while the debt pile has grown to a monstrous size.

The problem Japan presently faces can thus be defined as follows:

After the crisis of early 1990’s, the leaders of Japan decided not to let the environment to crash, due to e.g. cultural issues. In Japan, bankruptcies are considered high-profile frequently leading to suicides. While the bailout of the nipponese economy was understandable culture, the fact is that the restructuring of the nipponese economy after the financial crisis was an utter failure. Another country which experienced a financial crash at the same time, but recovered rather a remarced, is Finland.

Currence crisis

Currence and debit crisis tend to be profoundly intertwined. This is due to the fact that the abroad exchange value of a currency reflects the trust of global investors and businesses on the keeper of the currency, i.e. the government of a country.

Essentially, a currency crisis or a crash is an “attack” on the exchange value of the currency in the markets. If the abroad exchange (FX) rate is fixed or pegged, this attack will test central banks (the monetary authority) commit to the peg. The current view is that the timing of the attacks is not predictable. If the FX-rate is fixed or pegged, marketplace partners anticipate the policy of monetary authority will be inconsistent with the peg and they will effort to force authorities to abandon the peg, thus validating their effects.

What matters for speculators are the interior economical conditions with respect to external conditions set for the currency (like table FX-rate) . If these are incompatible in any meansful way, like erstwhile the government has an different debt burden, monetary authorizations face a trade-off between external and home goals for the exchange rate. In these circuits, random shocks in the abroad exchange markets, called sunspot, can trigger an attack on the external value of the currency. This means that, erstwhile interior economical conditions are deteriorating, due to e.g. an unustainable sovereign debit load, random events or shocks, can break the trust of investors leading them to sale the currency in the exchange markets causing the (external) value of the currency to drop abruptly or even to crash.

If a country holds a large external debit saw, a cracking currency will naturally increase its (foreign-currency) value threeing to make a wave of defaults. This applications to private entities, as well as to local and central government. A currency crash is frequently expected to lead to interest rate estimates by the monetary authority to defend the FX-rate of the currency. However, if the government holds a large amount of debt, higher interest rates can easy win the government under interest payments, which will yet lead to a sovereign default. Rising interest rates would lead to further detection of trust by investors in the currency of a highly identified government. This is why the Bank of Japan is trapped. If it would start to rise rates, the debit service burden of the nipponese government would rapidly become unsurmountable.

Conclusion

The bailout of the nipponese economy in early 1990s, which caused the tramp in productivity leading to the very advanced independency of the nipponese government, is the main Culprit behind the ‘flash crash’ of the nipponese Yen. On April 26, it seems, and the ‘sunspot’ has tried the selling. The consequence of the monetary authority, i.e., the BoJ, was to start to defend the yen at USDJPY pair of 160. Its intervention (buying of yen) pushed the pair to under 153 on May 3, where it has started to creep back up.

As the underlying problems of the nipponese economy have not gone anywhere, the attack on the yen in the markets is likely to proceed and escape, again, at any point. The question is, what is the breaking point in the USDJPY pair after which investors start to breathe? Moreover, we should remember that monetary authorizations have their limits, while markets don’t. Thus, it is very likely that the currency crisis of Japan has but just started. See my another post for analysis on its implications.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 05/11/2024 – 19:50