While preparing to compose this book, I reviewed a large part of Polish historical and public statements on Denikin and Piłsudski. 90 percent of them duplicated the position of the Pilsudian propaganda, whether his supporters or opponents do so.

Narration is in most cases the same – Denikin did not recognise Poland's independence, wanted the 1914 border, agreed at most to autonomy, was not inclined to any concessions, was an enemy of Poland, was a “reactionist” and wanted to reconstruct “self-robot”. In a softer version it is said that, yes, he recognised Poland's right to independence, but only within ethnographic limits (which is true), but only temporarily, due to the fact that after the win, the Polish independency would have rapidly liquidated, due to the fact that Russia would have had support in the dispute with the Polish Western countries, he was not inclined to talk and put Poland into unacceptable conditions. The general conclusion is: Piłsudski did well not to aid him fight the Bolsheviks.

I promised, however, that I would begin this review with the position of the only politician and publicist of the national camp, and not only of the camp who agreed with the position Józef Mackiewicz. He was. Oh, my God. I mentioned the first installment of the discussion between Mackiewicz and Józef Lobodowski in London “News” from 1946 to 1947. Gierty besides joined the discussion, publishing the text entitled “Poland a Denikin” ("News", No. 4 (95) of 25 January 1948, p. 3 – the full text is included in the annexes). The key conviction of the article was this: “In Poland, the Russian counter-revolution was considered more dangerous to us than Bolshevikism. This was undoubtedly a large mistake. To any extent, the narrow and doctrinal hatred of the Tsar, which obscured the view of Russia as specified and of its forces, has contributed to this error. It is clear that Denikin's triumph was in our interest, and if it was impossible, it was possible to drag his agony... I besides cannot agree with the view that the Denikina movement did not have a chance of triumph as born on the outskirts of the Russian state. The Bolshevik governments in 1919 passed a crisis, their being hung by a thread, insignificant shifts of forces could have been about their fall or about their being pushed to any another periphery. In critical moments of large struggles, erstwhile the tide weighs, a slight change in the situation can sometimes be reversed.”

He returned to the case after Mackiewicz published the fresh “The Left Free”. In letters to the author, Gierty completely agreed with his conclusions. In a letter sent on September 23, 1968 from London, Gierty wrote:

“I met your book ‘The Left Free’. [...] I disagree with you in most views on Polish politics, on the planet situation, on the past, on human life. But there are points where we agree. You wrote a lot in your book about Poland's aid (i.e. by Piłsudski) to kill Denikin. You besides wrote – which I did not know – but what makes me believe – that Piłsudski deliberately rushed to conclude a truce and peace-preliminaries in 1920 to aid the Bolsheviks to take Wrangl down. There was never uncertainty for me that in the conclusion of the rysian peace, and earlier preliminaries, the function of Piłsudski was indeed decisive. Grabski, a erstwhile associate of the PPS and an opponent of Dmowski, considered a nationalist, but in fact only half a nationalist, conducted negotiations in Riga going against Dmowski's politics, who wanted to join Poland Minsk, Bobrujska, Polock, Kamieniec Podolski, Mozyrz and Dyneburg. Piłsudski himself selected a ‘delegation’ of the parliament [for truce talks and then peace talks in Riga]. [...] I didn't realize what Piłsudski wanted in all this. Well, thanks to you, I understood: he wanted to knock Wrangle down. (Naturally, too, and it was always clear to me that Piłsudski, having reconciled with the essence of the program ‘incarnation of the east lands’ to Poland, due to the fact that his national program lost, wanted this program [i.e. incorporate] to compromise and limit by utilizing tiny caliber seismic policies, specified as Grabski or Dąbski, and by renunciation of Minsk, Podolski's Stone, etc., and by devoting blame for it to the Sejm.)

I was always of the opinion that we should have helped Denikin: not on a large scale, due to the fact that we could not jeopardize Poland's interests for Russia, we should have been primarily defending our own interests [...] Bolshevism should have been helped to break. And as for our national interests [i.e.] In spite of appearances, white Russia would be far little dangerous to us than Bolsheviks. Above all, she would be more weakened, on the inside subdued and without abroad resistance, thus doomed to search good relations with us. [...]

On October 7, 1968, Gierty returns to this subject again.“ Thank you kindly for your gracious letter. [...] About the anti-bolshevik crusade. Normally, all nation has a right and even an work to defend its own interests. But there are situations erstwhile you gotta participate in a crusade. But specified participation cannot be suicide and cannot be sacrificing 1 nation to another. The effort must be proportional to the possibility. For example, even if Poland was completely free at the moment, it would not be morally obliged to embark on an expedition to Cuba to release it from communist rule. Nor with an expedition to Biafra to save the Ib people from being slaughtered by Muslims from North Nigeria. These matters are beyond our scope – and our responsibilities. Similarly, erstwhile it comes to civilian war in Russia, we had a moral work not to disturb the ‘white’ Russians in their efforts, and even (in the name of the Christian and human affairs) we had a work to aid them in the degree that we could afford it without committing suicide. [...] Defeating Denikin by the Mikashevsky truce – it was a crime”. (Fragments of these letters were published by Prof. Andrzej Nowak in the periodical "Arcana", 2007, No 2-3 (74-75), pp. 184-204).

He draws attention to the emphasis on moral issues, but besides to Giertych's cut-off from Stanisław Grabski's policy, which was, at least until the mid-1920s, the leading politician of National Democracy. Giertych was in these categorical letters in the courts (the strategy in Mikaszewiczy is “criminal”), fundamentally completely coincident with the line of Joseph Mackiewicz's thinking. Was this the consequence of his cold analysis, or was it just another argument he could make against Piłsudski? most likely both. Of course, Gierty did not change his mind, wrote in the same kind as early as 1948, but now he was more convinced of his conclusions and more radical.

But it's not over. In 1974, Gierty, irritated with an attack on him from the “Polish Voice” in Buenos Aires, which repeated all the lies known to us (again to this day), including that Denikin did not recognise Poland’s independency – he published a brochure entitled “About Russia, Communism, German danger, Dmowski’s and Denikin’s politics: Again about Russia and Germany, and about China and Jews; How the communists were facilitated by triumph in the Russian civilian War". The part concerning Denikin is published in annexes. Here I quote only the beginning: “The fact that Denikin recognized the full independency and sovereignty of Poland is simply a fact so uncontested and so comprehensively documented that I do not request to deal with this issue. I will confine myself to quoting the contents of the toast that Denikin raised on 13 September 1919 at the banquet in Taganrog, issued to welcome Gen. Karnicki's mission sent by Piłsudski to make contact with Denikin." In this fight, Giertych utilized already known historical facts and papers that appeared in public space, and which contradicted myths spread by Piłsudski defenders.

Denikin Gierty besides referred to the subject in an extended essay entitled “Piłsudski and England” ("Communications of the Roman Dmowski Society", notebook I, London, 1970/1971, pp. 425-515). The full was devoted to the function of England in Polish politics over many years, but there was besides a subject concerning 1919. It was crucial in this text to respond to the thought of a large Ententa operation aimed at destroying Bolshevikism and allowing white Russia to win. The concept rapidly fell (supported by Ignacy Jan Paderewski, but besides partially by Dmowski). According to Giertych, who studied papers of the British abroad Office, Piłsudski was to dream of the function of politician of occupied Russia, which would satisfy his sense of revenge on old Russia. This is not entirely convincing, but another message by Giertych is important:

"The thought of the universal crusade against Bolshevikism was in 1919, simple, right. But specified a crusade, if it had any chance of success and any sense, should have been the work of powerful and long-standing peoples. It should besides be done in agreement with the Russian people (its anti-bolshevik forces) alternatively than in the form of conquest by the nation, like ours, suspected by the Russians of anti-Russian intentions. American, English French, nipponese troops should have marched to Moscow. Our function in specified a crusade – the function of a rebuilding nation – should have been to keep our own front and organize our own, infected with the revolutionary chaos of the Kresów (...) The Moscow Crusade, in which we would play a major function and sound the main burden of effort and victims, would have ended, after we had bled out thoroughly, with a terrible disaster and most likely a breakdown of our independence. It's not easy to conquer Russia! We found this in the seventeenth century in the years of Żółkiewski, and Napoleon and Hitler later found it. The task of conquering Russia proved besides hard for us even in our power age; in our capabilities in 1919 it was a task only individual who could be completely irresponsible could think of."

Finally, a summary of 40 years of reflection on this subject, which he concluded in his outline of Poland's past published in 1986. He wrote there, among others:

"Theoretically, there were 2 possibilities: to get active in the Russian civilian war and aid to win, in the name of the defence of Christianity and the conventional European order of the “white” side, or to admit that we do not care about Russian matters and to enter into Bolshevik peace with Russia. The first of these possibilities required an agreement with General Denikin, the most outstanding of the “white” camp chiefs in Russia, holding power throughout confederate Russia in 1919. He prepared – having captured the town of Eagle – for the final offensive on Moscow and to overthrow Bolshevikism in Russia. He addressed Poland with a proposal that Poles should make an offensive by Mozyrz to the town of Homla on the east side of Dniepr and thus cut off crucial forces of Bolsheviks. It was a turning point in the Russian civilian War: Polish action, tiny and comparatively easy, could have settled the destiny of the Russian civilian War towards anti-bolshevik. But Poland could not undertake specified an action, without the assurance from Denikin that it would recognise the fair Polish-Russian border, that is, the Dmowski line. However, attempts to arrange with Denikin were not made on the Polish side, and his proposal for an alliance was left unanswered. Even the other happened: Piłsudski concluded (in Mikaszewiczy, about November 1, 1919) a quiet truce with the Bolsheviks, ensuring that Poland would not undertake an offensive against them and thus they could pull troops from the Polish front and throw them against Denikin. Piłsudski preferred the triumph in Russia of the Bolsheviks over the triumph of white Russia and played a function in the Russian civilian War as a tilting factor."

He concluded: “Perhaps our alliance with Denikin was indeed impossible, so we could not support him. (Although he had a knife on his throat, and in specified a position you are not usually relentless.) However, it is simply a fact that we have not tried to scope an agreement with him and that we know nothing about his final position and supported the Bolsheviks." (Jędrzej Giertych, "Thousand of the past of the Polish nation", London 1986, pp. 67-68).

In this final conviction we can see any softening of the courts, e.g. in relation to the opinions expressed in letters to Józef Mackiewicz from 1968, but the general message has not changed. Jędrzej Giertych was the publicist and emigration politician, who was most closely approached by Józef Mackiewicz. On the another hand, it would be interesting to learn the opinion of Mackiewicz himself about the letters he received from Gierty, especially since he was not a sympathizer of the national camp, on the contrary.

During the discussion after the publication of Józef Mackiewicz's book “Left free” he besides spoke Tadeusz Piszczkowski (1904-1990), associate of the National Party, writer of “Polish Thought”, author of 2 crucial books on Polish past – “Rebuilding Poland 1914-1921. past and Politics” (Orbis – London 1969) and “England a Poland 1914-1939 in the light of British documents” (Oficin of Poets and Painters – London 1975). This first book contains his texts on the restoration of the Polish state previously published in “The Polish Thought”. 1 of them afraid the case of Denikin ("Left or Free Right?" – the full is included in the annexes), which was a mention to the title of the fresh by Józef Mackiewicz. Piszczkowski did not hold specified a categorical position as Gierty, he was even willing to accept Piłsudski’s ration: “But was he to do otherwise? Was he to aid “white” to whom he had no sympathy (“they did not like” – in the words of Józef Mackiewicz) and who, although they recognized the right of Poland to independency in accordance with the March 1917 declaration of Fr Lwów, repeated the expression about ethnographic boundaries and the Polish-Russian border substance postponed to the Russian “constitution” (...) The triumph of the Bolsheviks in the civilian war could so seem to Piłsudski a lesser "evil" for Poland – and the final proceeding with them was easier than with the "white" in case of their victory. However, he did not resolve the unification or who was right: "So it was a controversial substance – and Piłsudski may have been mistaken in his calculations, for example, he may have underestimated the forces which the Bolsheviks were able to establish if it had come to clash with Poland".

At the same time, he felt that Piłsudski’s mistake active something completely different: “In Piłsudski’s primary relation with Russia, only negative. Although he has never clearly formulated his ‘Russian programme’, his full proceeding revealed that it was an anti-Russian programme and a deep distrust of Russia. (Think Poland, April 15, 1966, p. 3). And at this point you gotta agree with the author, he touched the essence of the substance that we have been considering for so many years. A rational global policy based on phobias, fears, historical prejudices and – let us not be afraid of this word – contempt and hatred. This continues all the time to this day. Therefore, in my opinion, Piszczkowski's conclusion is of large importance. But why did he disagree with Mackiewicz's position? due to the fact that he was an expression of the authoritative position of the national camp, and in this case it was not so unambiguous. Piszczkowski mentioned Dmowski's line, the concept of east borders of Poland, which Denikin questioned. For this reason, he had to formulate his conclusions as he did in this article.

It was inactive very balanced. Earlier opinions of national camp politicians and historians were much more "antidenic". As an example, I will give 2 – Stanisław Grabski (1871-1949) and Prof. Władysław Konopczyński (1880-1952). Grabski was 1 of the leading politicians of the National Democracy in 1919, president of the Parliamentary Committee on abroad Affairs, knew very much, although he could do very little, due to the fact that Piłsudski did not have the habit of consulting his actions with anyone, the more with the leaders of the endation. Grabski accepted the decision of Polish troops to the east (to the Dmowski line), questioned the national program, including, above all, the enemy of supporting the construction of Ukraine. As for the attitude towards white Russia – he did not disagree much from Piłsudski. In his memoirs. written at the end of his life, in 1946-1948, he wrote about the arrival of general emissaries in Warsaw in the summertime of 1919. Denicin:

“This mission was, of course, directed to the chief of our armed forces, Marshal Pilsudski. But her boss made a want to see me too. He was most likely counting on my support for his proposal in Piłsudski. However, I did not consider it possible for the Committee on abroad Affairs or even myself to intervene in this matter. Denikina's delegate (who was a Cossack Ataman, whose name is 1 I can't remember) avoided any discussion about the future Polish-Russian border, claiming that not only he, but besides Denikin, can make no commitments in this regard; only the legitimate government, which will include governments in Russia after the fight against Bolshevikism, will have the right to enter into a treaty with Poland that would possibly depart from the Russian Empire in exchange for the assistance shown in the fight against the Bolshevik revolutionary coup. According to this, Poland would fight not to recover the lands taken from it during the partitions and inactive under the strong influence of Polish civilization despite the 100 years of almost their rusification, but to reconstruct in Russia the regulation of these spheres and those people who led before the war in this very russification policy – in order to reflect on our border on their gracious assessment of the favour we have given them.

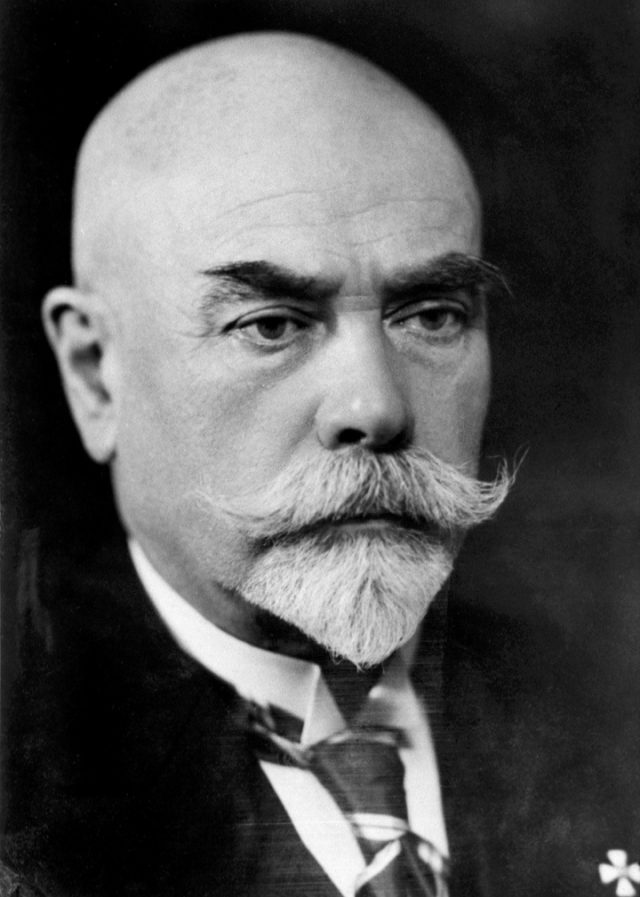

Anton Denikin on emigration

So I was not amazed erstwhile I found out that eventually, after longer negotiations, he besides sent his representatives to Denikin, Piłsudski refused to cooperate militarily with him. At the same time, it was told in Warsaw that at the same time Marchlewski had secretly come to him and that he had stopped military action in Volyn and Polesia, which helped the Bolshevik armies to break Denikin's offensive. I have never been able to verify the veracity of this version. But if he had actually done so, I would not take it against him, due to the fact that doubtless if Moscow and Petrograd were conquered by white generals not only England but besides France, in which all somewhat wealthy citizen owned Russian state bonds, would stand entirely on our east border on the side of Russia. I was not delighted at the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, but I was much more afraid of the return of Tsarist Russia with the nationalist call: the oneinaja non-dielimaya (one indivisible)’. (Stanisław Grabski, "Memoraries", Volume 2, Reader –Warsaw 1989, pp. 126-127).

Two remarks – Grabski intended to print his memoirs in the book “Reader” in 1948. He himself was then (until the 1947 election) vice-president of the National Council. In his political biography we have a socialist episode, he was 1 of the founders of PPS (1892). Only in the early 20th century did he join the National League. This part of his résumé was very useful to him after 1945, and he willingly exhibited it. For example, describing the actions in Russia in 1918 to save the 2nd Polish Corps, which went east and was commanded by Gen. Joseph Haller, he mentioned that he had made the Bolsheviks neutral due to the fact that he met 1 of his Galician socialist friends from the 1990s, a judaic notabene. And the second remark – the analysis of Grabski's message from 1919 does not indicate that he had specified a unanimous negative opinion about white Russia. He demanded that political relations be established quickly, in accordance with Dmowski's guidelines. It is actual that the starting point for talks with the Russians was to be the territorial programme outlined by the National Committee of Poland. So we can say that erstwhile writing Grabski's memoirs, he bent his communicative somewhat to the requirements of the times in which they were created.

The second example is more unambiguous. Prof. Władysław Konopczyński was a prominent, if not the most outstanding historian of modern Poland, called the “smack” of archives, the author of specified epochal works as the “Barsk Confederation” or “The Acts of Modern Poland”. During the Nazi business he worked on writing the biography of Józef Piłsudski. It waited for a very long edition, due to the fact that until 2023! We read about Denikin here:

“Denikin after Kołczak and Judenich, and before Wrangle recognized by the entent as the heiress of Tsarist Russia, powerfully supported by the French and English, acted from the black sea and there were moments erstwhile he had already reached Moscow 100 kilometres... Coalition diplomats, as well as any Poles, hoped for Piłsudski, that in the war with the Bolsheviks he would gladly usage this reactionary diversion. An highly hard task opened up to Polish politicians. specified Russians as could treat Poles as equal friends, specified as the Slavic brothers, were few; possibly they would have been Boris Sawinkov, a typical of the “democratic committee”, based on social revolutionaries (...) and even little were they fighting with Bolsheviks for Anglo-French money generals: Judenich, Kołczak, Denikin proclaimed the slogan of Russia “one and the other”. If 1 of them had taken control of the situation, and restored the carat, surely England and France would have supported the second in the disputed issues between Poland and Russia." In addition, Konopczyński wrote that "Piłsudski knew Russians better than Dmowski" and was warned by Gen. Karnicki about Denikin's position, which discouraged him from supporting his army. (Wladysław Konopczyński, “Piłsudski a Polska”, Wydawnictwo Giertych, Kórnik 2023, pp. 121-122).

Despite criticism of the national program, Konopczyński agrees quietly with Piłsudski about Denikin. The opinion that Piłsudski knew the Russians better than Dmowski is, of course, controversial – Piłsudski faced either Russian revolutionaries or people with repression apparatus, Dmowski had many connections in the establishment and in the governmental spheres. Both Piłsudski and Dmowski grew up in the Russian partition, they knew Russian language and culture. However, their perception of Russia was different, although 1 could agree with the thesis that after 1918 they were both someway retaliating on Russia. Finally, Konopczyński writes completely incorrectly about Denikin's position towards Poland, does not even effort to present his reasons and repeats slogans about the danger of "returning the carat", which was in 1919 the main panic of the anti-Denikinian propaganda filmed by Piłsudski and PPS camp. The case of Konopczyński shows that it fell on susceptible ground not only among supporters of these camps. 1 of these dogmas cultivated to this day is the portrayal of Boris Sawinkov as the only “good Russian”.

Jan Engelgard

This is part of the book “Russian Syndrome. The case of Gen. Anton Denikin from a historical perspective”, which is published by Capital Publishing home and Miśmy Polska Publishing House.

Think Poland, No. 39-40 (22-29.09.2024)