Elections And Devaluations

Authorized by Yves Smith via NakedCapitalism.com,

Yves here. It’s revealing that Serious Economist Jeffrey Frankel limits himself to third-world examples in his case studies below on post-election deductions.

Perhaps it would be unseemly to look at, say, the US, UK, Japan, South Korea, or even Australia (admittedly the later and Canada have their currency values virtually affected by community prices). Of course, Frankel might conclude that any politically-related currency action in an advanced economy would not amount to a depreciation-level decline. After all, they have independent central banks.

As many, including your humble blogger, have noted, The US is moving a very hot fiscal policy along side tight monetary policy. Hence America has persisted in having solid to very strong groaf figures, leading the Fed to individual in tight monetary policy. All of that has led the dollar to trade at very lofty levels.

One has to think the dollar will start to reverse close the election, say in October. But inflation has been very sticky, and it’s interesting rates that are buying the greenback, so it might stay comparatively strong even past the election. In addition, the US has, at least since the Clinton Administration, has had an exploit strong dollar policy. Weak currencies and financial centers do not co-exist happily. The Fed has historically not cared a which is about what moves in interesting rates have done in terms of in and out flows to emerging economies, who are routinely whipsawed by hot money moves. 1 wonders if we will evenly see the Fed become more interesting to the value of the dollar.

Any readers who are currency-knowledgeable are encouraged to opinion on which countries might look more attractive as King Dollar retreats from its current high.

By Jeffrey Frankel, Economist and Professor, Harvard Kennedy School. Originally published at VoxEU

An unprecedented number of voters will go to the polls globally in 2024. It has long been noted that incumbents tend to engage in expansional fiscal (and where possible monetary) policy in the run up to elections in order to buy the environment and so their electoral prospects. This column extensions this concept to look at exchange rates and finds that currencies freely depreciate following an election as the inclusive’s beneficiaries to overvalue the currency in the run up to the election are unwound and the fresh government comes to terms with depleted reserves and current account woes.

Lots of countries are voting, with 2024 an unprecedented year in terms of the number of people who will go to the polls. Recent elections in a number of emerging marketplace and developing economies (EMDEs) have demonstrated again the proposal that major currency deviations are more likely to come immediatly after an election, alternatively than before one. Indeed, Nigeria, Turkey, Argentina, Egypt, and Indonesia are 5 countries that have experienced post-election derogations within the last year.

The Election–Devaluation Cycle

Economists will retrieve a 50-year-old paper by Nobel Prize winning prof. Bill Nordhaus as fundamentally initiated investigation on the political business cycle (PBC). The PBC references to government’s general inclusion goods fiscal and monetary expansion in the year leading up to an election, in hops of the inclusive president, or at least the inclusive party, being re-elected. The thought is that growth in output and employment will accelerate before the election, boosing the government’s popularity, thus the major costs in terms of debit streets and inflation will come after the election.

But the seminal 1975 paper by Nordhaus besides included the prediction of a abroad exchange cycle partially applicable for EMDEs. That is the proposal that countries mostly see to prop up the value of their currencies before an election, spending down their abroad exchange reserves, if necessary, only to undergo a declaration after the election.

Nordhaus Gates: “It is predicted that the performance with fates of reserves and balance of payments defaults will be large in the beginning of electrical regiments, and little toward the end. ... The basic difficulty in making intertemporal choices in democratic systems is that the awesome weighing function on consumption has affirmative weight during the electoral period and zero (or small) weights in the future.’

The devaluation may be undertaken deliberately by an incoming government, choosing to get the unleasant step – with its unpopular exercise of inflation – out of the way while it can inactive blame it on its predecessors. Or the depreciation may take the form of an overwhelming balance-of-payments crisis shortly after the election. Either way, a government has an interesting to circular global reserves during the early part of its word in office, and to spend them more freely to defend the currency toward the end of its term.

A political leader is almost twice as likely to loose office in the six months following a major devaluation as otherwise, especially among presidential democracies (Frankel 2005). Why are they devalued so unpopular that government feat to undertake them before elections? In the conventional textbook model, a devaluation stimulates the economy by improving the trade balance. But devaluations are always inflationary in countries which import at least a condition of the basket of goods consumed. Furthermore, deviations in EMDEs frequently are contrasting for economical activity, partially via the approach balance sheet effects on these home borerowers who had incurred debits denominated in dollars.

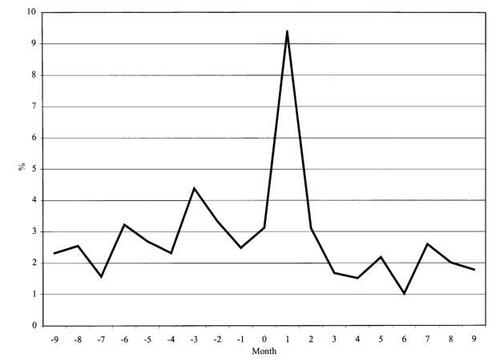

The explanation of the political devaluation cycle was developed in a series of papers by Ernesto Stein and co-authors. 1 might think that voters would want to go up to these cycles and vote against a leader who sneakily postponed a needed exchange rate adjustment. But given a catch of information about the actual nature of the politicals, voters may in fact be active ratio. Figure 1, from Stein and Streb (2005) shows that deviations are far more common in the intermediate aftermath of changes in government. (The example covers 118 episodes of changes, exclusive coups, among 26 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1960 and 1994.)

Figure 1 Average default pattern before and after elections

Source: Stein and Streb (2004).

Some Devaluations Over the Past Year

Many EMDEs have been under balance-of-payments force during the last 2 years. 1 origin is that the US national Reserve raised interest rates sharply in 2022-23 and is now leaving them higher for longer than markets had been experienced. Consecently, global investors find US treatment bill more attractive than EMDE lounges and securities.

A good example of the political devaluation cycle is Nigeria. Africa’s most populous country held a contentious presidential election on 25 February 2023. The incumbent, who was term-limited, had long utilized abroad exchange intervention, capital controls, and multiple exchange rates to avoid devaluing the currency, the naira. The fresh Nigerian president, Bola Tinabu, was inaugurated on 29 May 2023. 2 weeks later, on 14 June, the government devalued the naira by 49% (from 465 naira/$, is 760 naira/$, computed logarithmically). It shortly turned out that this was not adequate to reconstruct equilibrium in the balance of payments. At the end of January 2024, the government abandoned its effort to prop up the authoritative value of the naira, devaluing another 45% (from 900 naira/$ to 1,418 naira/$, logarithmically).

A second example is Turkey’s selection in May 2023. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had long pursued economical growth by obliging the central bank to keep interest rates low – a populist monetary policy that was easy ridiculed due to the president’s intention that it would reduce soaring inflation – while simultaneously intervening to support the value of the lira. The government guaranteed Turkish bank deposits against depreciation, an costly and unsustainable way to extend the currency overvaluation. After the elections, the lira was immediately devalued, as the explanation predicts. The currency continued to depreciate during the reminder of the year.

Next, on 19 November 2023, Argentina selected a surprise candidate as president, Javier Milei. frequently described as a far-right libertarian, he comes from no of the established political parts. He campaigned on a platform of diminishing Sharply the function of the government in the economy and abolishing the ability of the central bank to print money. good to see you in on December 10. 2 days later, on 12 December he cut the authoritative value of the peso by more than half (a 78% devalue, computed logarithmically, from 367 pesos/$ to 800 pesos/$). At the same time, he took a chain Saw to government spending specified as energy subsidies rapidly achieved a budget supplus, and initialized sweeting reforms. Argentine inflation restores very high, but the central bank stopped losing abroad reserves after the default, again as predicted by the theory.

A 4 example is Egypt, where president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi just started a 3rd term, on 2 April 2024. The economy has been in crisis for any time. Nevertheless, the government had included its overwhelming re-election on 10-12 December 2023 by postponing unleasant economical means, not to comment by preventing serious views from running. The highly expected devaluation of the Egyptian pour, came on 6 March 2024 depreciating 45% (from 31 egyptian Pounds/$ to 49 Pounds/$, logarithmically). It was part of an enhanced-access IMF programme, which besides included the usual unpopular monetary and fiscal discipline.

Finally, in Indonesia the wide liked but term-limited president Jokowi is shortly to be successful by the defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, who is little easy liked but was backed by the inclusive in the 14 February election. The rupiah has been depreciating always since the 20 March announcement of the result of the contentious presidential vote. It fell besides to an all-time evidence low against the dollar on 16 April.

What's next?

Of course, the association between elections and the exchange rate is not inevitable. India is undergoing elections now and Mexico will in June. But never sees especially in request of major currency adjustment.

Venezuela is scheduled to hold a presidential election in July. As with any another countries, the selection is expected to be a sham due to the fact that no major opposition candidates are allowed to run. The economy is in a shambles due to long-time mismanagement features hyperinflation in the last past and a chronically overvalued bolvar. But the same government that fundamentally outlaws political opposition besides fundamentally outlaws buying abroad exchange. So, equilibrium may not be restored to the abroad exchange marketplace for any time.

It stave off devaluation, these countries to more than just spend their abroad exchange reserves. They frequently usage capital controls or multiple exchange rates, as opposed to allowing free financial markets. That does’t introduce the Phenomenon of post-election deductions; it just works to insulate the governments a bit longer from the needed to adjust to the reality of macroeconomic fundamentals. Unfortunately, many of these countries besides neglect to let free and fair elections, which works to besides insulate the government from the needed to respond to the voters’ verdict.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 05/14/2024 – 22:40